Recursive Language Models: the paradigm of 2026

How we plan to manage extremely long contexts

LLM agents have become significantly more useful over the course of this year. They are now capable of implementing complex changes in large codebases autonomously, often reading and editing dozens of files, searching the web, and maintaining context even over the course of multiple such complex requests.

These capabilities require the use of vast numbers of tokens.

But that, in turn, is difficult for current LLMs: per-token costs rise linearly with the context length, while the performance of even the best models drops with it. A well-known phenomenon at this point is context rot, the reduction of LLM capabilities as contexts grow in size. And even though changes to architecture and training data have caused, and will continue to cause, much progress to address these challenges, there is one thing that is complementary to both, and has consistently been a huge multiplier to LLMs’ effective context length: scaffolding.

Claude Code, OpenAI's Codex, and similar TUI systems tend to use file-systems and context compression by LLM summarization at regular intervals as the basis of their scaffolding. This effectively leads to a succession of agents, all connected to each other by a prompt and the state of some set of files.

A different approach to the context problem is "context folding". Its goal is to have a continual, growing rollout, while managing the context window itself (instead of external files) in order to keep it short. This is compatible with the file-based scaffolding, as an LLM using context folding looks just like a normal LLM from the outside, and thus, it is a way to further prevent context rot and manage costs. Some examples are:

- Scaling Long-Horizon LLM Agent via Context-Folding: the agent can actively

branchits rollout, andreturnfrom the branch; within the branch, it retains the full previous context, but after returning, only a self-chosen summary of the branch remains in the context window - AgentFold: Long-Horizon Web Agents with Proactive Context Management: every one of the agent's actions produces both a result, and a summary of the action and the reasoning that led to it. These summaries can be hierarchical, consolidating the lessons from multiple actions into a single point, or retaining per-action summaries

- Agentic Context Engineering: Evolving Contexts for Self-Improving Language Models: a three-agent system with a Generator that uses the current knowledge base for creating the rollout, a Reflector which takes lessons and information about the generation and about the current state of the knowledge base, and a Curator for taking the Reflector's lessons and adapting the knowledge base with them in a structured manner

However, we at Prime Intellect believe that the simplest, most flexible method for context folding is the Recursive Language Model (RLM), introduced by Alex Zhang in October 2025 as a blog post, and now available as a full paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.24601. It is now a major focus of our research.

The RLM allows the model to actively manage its own context. This approach is more in line with The Bitter Lesson than the ones presented before; it enables training directly with the RLM scaffolding and getting better and better, learned context folding; and it never actually summarizes context, which leads to information loss. Instead, it pro-actively delegates context to Python scripts and sub-LLMs.

We believe that teaching models to manage their own context end-to-end through reinforcement learning will be the next major breakthrough, enabling agents to solve long-horizon tasks spanning weeks to months.

In this article, we share our initial ablations with the RLM scaffolding on existing models called through APIs. In future work, we will be scaling the training of the RLM on environments that reward effective very long-horizon reasoning.

The RLM

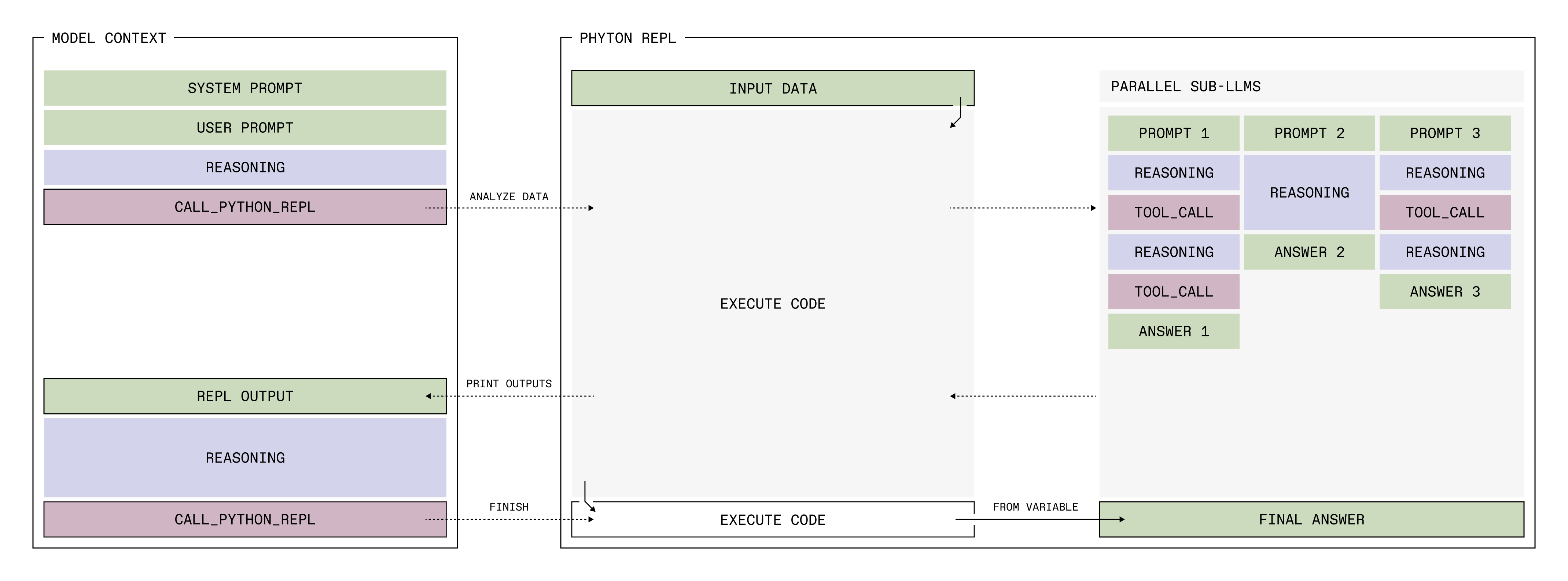

Rather than directly ingesting its (potentially large) input data, the RLM allows an LLM to use a persistent Python REPL to inspect and transform its input data, and to call sub-LLMs from within that Python REPL.

This enables several nice capabilities:

- Potentially huge input data, like PDFs or Datasets or videos, doesn't have to be loaded directly into a model's context, which makes the LLM leaner and avoids context rot

- The LLM can search, filter, and transform the context using Python functionality, avoiding the need to process redundant input

- It can use sub-LLMs--fresh instances of itself--to perform work for it, and programmatically pipe parts of the input data into them

These skills combined make it a great candidate for situations that typically require large context sizes.

We at Prime Intellect have implemented our version of the RLM in verifiers so that it is ready to be used in any environment—we do provide several RLM-based environments on the Environments Hub—and for training with prime-rl. It is still an experimental work-in-progress, but we have already added our own flavor to it.

The two most important changes required to understand the rest of the article are (1) that tools beyond the Python REPL can be used, but only by sub-LLMs; and (2) that the model can only provide its answer via an environment variable. The details are as follows:

- The sub-LLM calls can be parallelized

- The model has an

llm_batchfunction available in the REPL, through which it can process a batch of prompts in parallel

- The model has an

- The sub-LLMs can be given tools

- In fact, any tools you give the environment will only be usable by the sub-LLMs

- This decision was made because many tools produce a lot of tokens. Now, the main RLM doesn't have to see those tokens, and can instead delegate the work that requires tools

- As shown below, this strategy is very successful in our tests

- Any pip package can be installed

- The RLM is made aware of which packages are installed

- In math-python, for example,

numpy,scipy, andsympywere installed - The standard library is always available

- Code execution happens in isolated Sandboxes

- The RLM only ever provides an answer in a Python variable

- An

answervariable is initialized at the start of each Sandbox running the Python code; it's a dictionary with two keys:"content": The LLM can write into this as often as it wants, and it can delete or edit the content over multiple turns"ready": Only when this is set toTruewill the rollout end, and the answer be extracted from"content"

- At the start of each rollout,

answer = {"content": "", ready: False} - This setup allows the model to generate its final answer via a form of diffusion, which occurs over the course of its reasoning chain

- An

In our current implementation, both a prompt and extra input data can be given. The prompt is put directly into the RLM's context window, while the extra input data is available only programmatically. The only way for the RLM to view that data is to print it in the REPL. But since we limit the number of output characters from the REPL output that will be shown to the RLM in each turn (to 8192 by default, user-adjustable), the RLM is forced to make use of Python and sub-LLMs to work with input data.

Taking it all together, the RLM is powerful long-context agent, strong at tool-use, and extremely flexible. It is perfect for a world in which context is a sparse resource.

Experimental setup

The basic setup of all our experiments is to compare three scaffolds for the same environment:

- A standard LLM with whatever tools the environment normally provides

- The RLM

- The RLM with environment-specific tips (which will be explained later)

This tells us how a normal LLM compares to an RLM, and to an RLM that knows how its scaffold is best used in the given environment. We directly compare to an LLM because at its core, an RLM is an abstraction around a single LLM call.

The RLM is limited in its per-REPL-call timeout, which we set to 120 seconds unless stated otherwise. This helps when the RLM writes inefficient code, but also limits its use of sub-LLM calls.

Environments

The environments we chose are:

- DeepDive

- math-python

- Oolong

- verbatim-copy

We perform ablations on them using default settings (which were chosen before doing any experiments), and also ablate environment settings for Oolong and verbatim-copy.

Let's go through what they do and why we looked at them one by one.

DeepDive

DeepDive is a method for gathering data for Deep Research tasks by walking open knowledge graphs to create complex questions and verifiable answers, then obfuscating the questions via LLM re-formulation. A GitHub repo and a HuggingFace dataset exist.

Some examples:

To solve such problems, the models have three tools available to them:

search(query: str); use Google via Serper. Returns an enumerated list of Google results and the corresponding URLclick(index: int); "click" on one of the results from the previous search by providing the list-indexopen(url: str); open the given URL

These three tools are what's used in the original paper. However, open and click are redundant, and open is the more general tool. Since click requires not only the agent but the function itself to have knowledge of the previous search outputs, which is currently difficult to achieve in the RLM, we provided neither the RLM nor the standard agent with the click tool.

Why DeepDive?

DeepDive requires strong tool-use. It's tools also produce many tokens, open can produce tens of thousands of tokens (and that is with truncation, without that we've seen 1.5 million tokens and more). The tasks also often involve many subsequent tool-calls. Therefore, DeepDive tests how well the model using the RLM harness can make use of sub-LLMs with tools, how strongly that impacts the main RLM's context length, and at what cost in parallel sub-LLM calls.

Additionally, there is no extra input data for the RLM to use, so this environment tests the RLM's ability to work like a normal LLM, which is exactly what it looks like from the outside.

Environment tips for DeepDive

_ENV_TIPS = """

<env_tips>

Strategy for deep research tasks:

1. **Decompose the question**: Break the main question into multiple smaller, focused research sub-tasks that can be investigated independently.

2. **Parallel sub-LLM research**: Use `llm_batch()` to dispatch these sub-tasks in parallel. Each sub-LLM has access to web search tools (search, open) and can:

- Search for relevant information

- Open promising results to read full content

- Extract and summarize key facts

2. **Synthesize findings**: After collecting sub-LLM responses, combine and cross-reference their findings. Look for:

- Consistent facts across sources (high confidence)

- Contradictions that need resolution

- Gaps that require follow-up research

3. **Iterate if needed**: If the initial research reveals new questions or missing information, dispatch another batch of targeted sub-tasks. Repeat until you have sufficient evidence.

4. **Finalize**: Write your synthesized answer to `answer["content"]`, verify it addresses the original question, then set `answer["ready"] = True`.

Key insight: Sub-LLMs handle the verbose web content, returning concise summaries. This keeps your context clean while leveraging deep research.

</env_tips>"""

Default settings

We don’t ablate settings for DeepDive, meaning that no specific default settings are required.

math-python

math-python poses difficult math problems, and gives an LLM a Python tool to solve those problems.

Examples:

Why math-python?

The Python REPL is very similar to the Python tool that the standard LLM gets. However, there are two important differences between the two:

- The RLM has sub-LLMs available to it, and can therefore theoretically break the task down into subtasks, or let sub-LLMs evaluate its work

- The RLM has to manage much more complicated scaffolding. While it can keep things simple, it needs to be able to ignore a lot of complexity

Environment tips for math-python

_ENV_TIPS = """

<env_tips>

Use Python for calculations. The `sympy` library is available for symbolic math.

</env_tips>"""

Default settings

Like in DeepDive, we simply use the environment defaults.

Oolong

Oolong is a long-context eval with both a GitHub page and a HuggingFace dataset.

The dataset is split into synth, synth-with-labels, and real:

- The synth data is constructed by aggregating multiple existing classification prompts into one bigger prompt and asking the model to aggregate some quantity

- For example: take a dataset for classifying mails into "spam" and "no spam"; throw many of the example inputs into one prompt; and ask the model to count how many spam mails are contained within the prompt

- The synth-with-labels data is the synth data, but the classification (for example, "spam" or "no spam") is provided for each sub-prompt from which the data is created

- The real dataset is constructed from real D&D playing sessions that were recorded and from which some information was extracted

- For example: how often was xyz spell cast?

- For example: when did xyz happen?

Both the synth and real subsets involve many instances of classification and data extraction per prompt, followed by aggregation of the results. synth-with-labels only requires aggregation. The most important dataset is real, which we therefore choose for our default setting.

There is one complication: we only sample 50 prompts for these early evaluations, but the Oolong data is sorted by size, so sampling in the dataset order would only give us short input prompts. We therefore sample a uniformly random subset of 50 prompts from each of Oolong synth, synth-with-labels, and real, with the same random seed between all settings we ablate.

Why Oolong?

Oolong is a complex, long-context eval that many models struggle with, and it's what the original RLM blog post used. The RLM has much promise in this setting, because the long context is accessible to it only through the Python REPL, where sub-LLMs can help with the classification of parts of the context, while the RLM aggregates the results. It is therefore a good way to test how well the split between prompt and additional input data works, and the capabilities of long-context understanding of RLMs.

Environment tips for Oolong

_ENV_TIPS = """

<env_tips>

Strategy for long-context information retrieval:

1. Split the context into chunks (e.g., by paragraphs or fixed character windows with some overlap)

2. Write a prompt describing what to look for, then append it to each chunk to create a list of prompts

3. Call llm_batch() once with all prompts to scan chunks in parallel

4. Aggregate the relevant findings from the responses

</env_tips>"""

Default settings for Oolong

- default subset: real

Verbatim copy

LLMs often struggle to repeat complex texts verbatim. This is both a result of training, and an inherent limitation from sampling-based generation. To test this, we developed the verbatim copy environment.

It auto-generates data for the model to copy, and has several knobs to turn:

content_type: how the data is generated- "words": English word sequences

- "json": JSON formatted data

- "csv": CSV tabular data

- "codes": UUIDs and alphanumeric codes

- "mixed": combination of all types in one prompt (see

mean_fragment_lengthbelow to see how this is implemented) - "all": balanced mix across all types; each prompt has a random content type

target_length: the length of each repeatable sequence in characters. Achieved by over-generating and then truncating to the desired lengthmean_fragment_length: the mean length of fragments- We oversample the data for each prompt by generating a much larger batch than requested

- Say we have 4 initial prompts per final prompt

- Then, we take a random slice from each of those 4 prompts and put them together

mean_fragment_lengthcontrols the mean size of those slices (which randomly vary by ±50%)- The nice thing is that if we have "mixed" data, the prompt will be made up of slices from different data-types, which could lead to strange tokenization and weird texts; though even with a single data-type, it can have advantages like breaking json syntax in strange ways

All randomness is controllable via a seed, which we keep the same across experiments.

Why verbatim copy?

The RLM could theoretically help here: the model can write its best attempt at copying the input verbatim into answer["content"], without setting answer["ready"] to True, print it out, and then edit any errors with targeted Python functions. A simple answer["content"] = answer["content"].replace("<erroneous>", "<fixed>") could do the trick. While a normal reasoner could also write out parts of the string that it should repeat multiple times in its reasoning, there is no point to that: the final answer will still be one-shot for the entire response.

This helps explore how helpful returning an answer in a variable could be.

Environment tips for verbatim copy

_ENV_TIPS = """

<env_tips>

Strategy for verbatim copying:

1. Write your initial attempt to answer["content"]

2. Print answer["content"] to see exactly what you wrote

3. Compare carefully with the original text - look for typos, transpositions, missing characters

4. Fix any errors using string operations (slicing, replacement, etc.)

5. Only set answer["ready"] = True after you have verified correctness

</env_tips>"""

Default settings for verbatim-copy

content_type = "all"target_length = 500mean_fragment_length = 20

Models

We run our main ablations with GPT-5-mini. The reason is that initial experiments show that it is better at using the RLM scaffolding than the open-source models that we've tested. Additionally, the OpenAI API is significantly more stable than the OpenRouter API.

The open source models we do ablate in the end are all run through OpenRouter, with defaults set to z-ai for GLM 4.6 and GLM 4.5 Air, and nebius/fp8 for INTELLECT-3. We additionally tried using DeepSeek-v3.2 from google-vertex, but the model kept using the wrong function calling format, which invalidated our results. We also tried to ablate Xiaomi's Mimo-v2-flash, but the rate limits were too strict to get meaningful results.

It is very important to note that this is not meant to find out any model's absolute performance on a benchmark. We put no effort into tuning any hyperparameters or optimizing individual model performance in any way, and stick with default settings everywhere.

The comparison we care about is that between the LLM and the RLM; absolute performance doesn't matter, only relative.

Results

We will present the results in three sections:

- Across environments, using per-environment default settings (GPT-5-mini only)

- Within environments, shining more light on the behavior of some specific environments (GPT-5-mini only)

- For different models

Every plot will be paired with the command with which it can be replicated from verifiers sebastian/experiment/rlm branch, from the root verifiers directory.

Results across environments

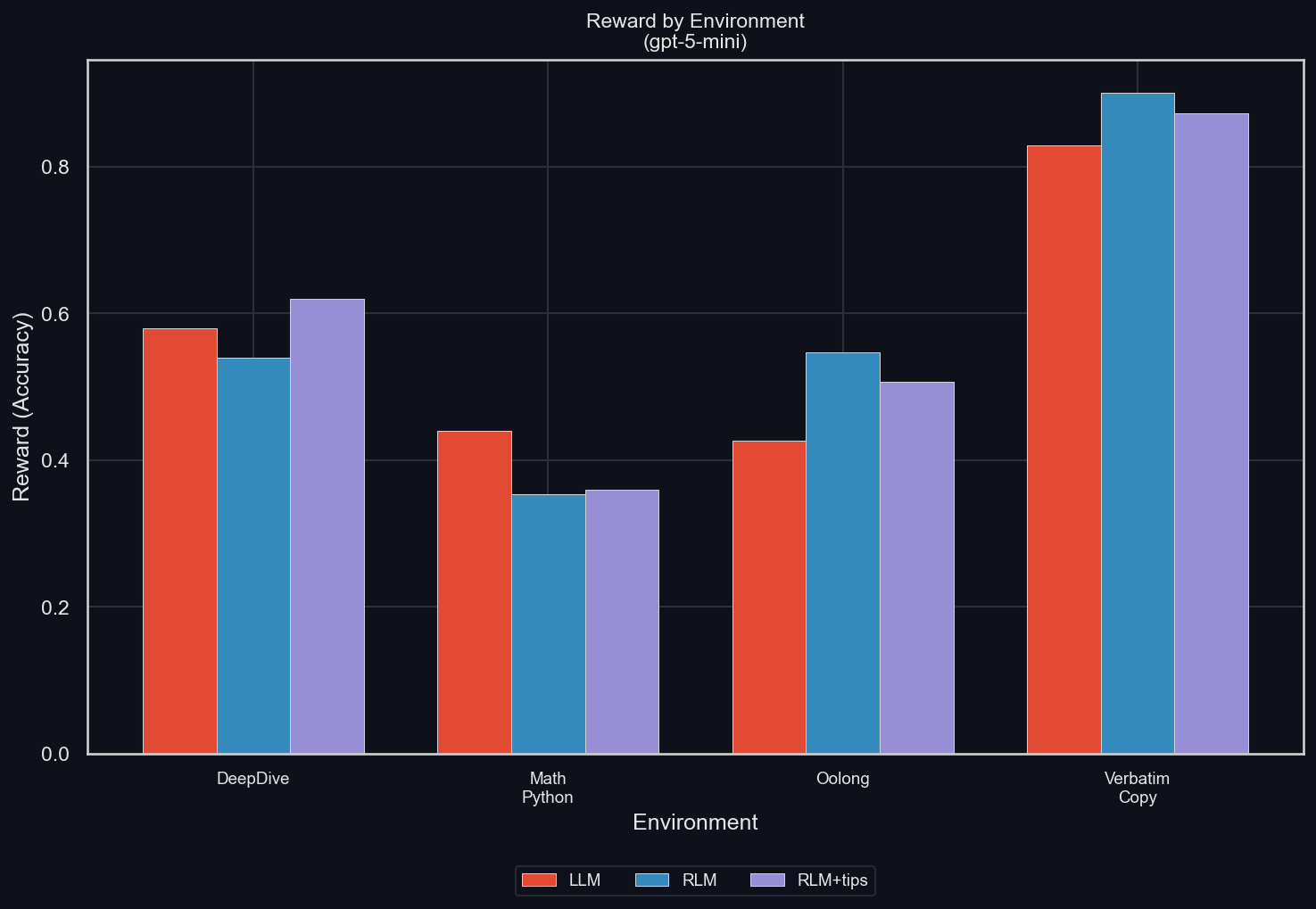

This gives us a good overview over which capabilities are helped or hurt by the RLM. It is run with default settings for each environment.

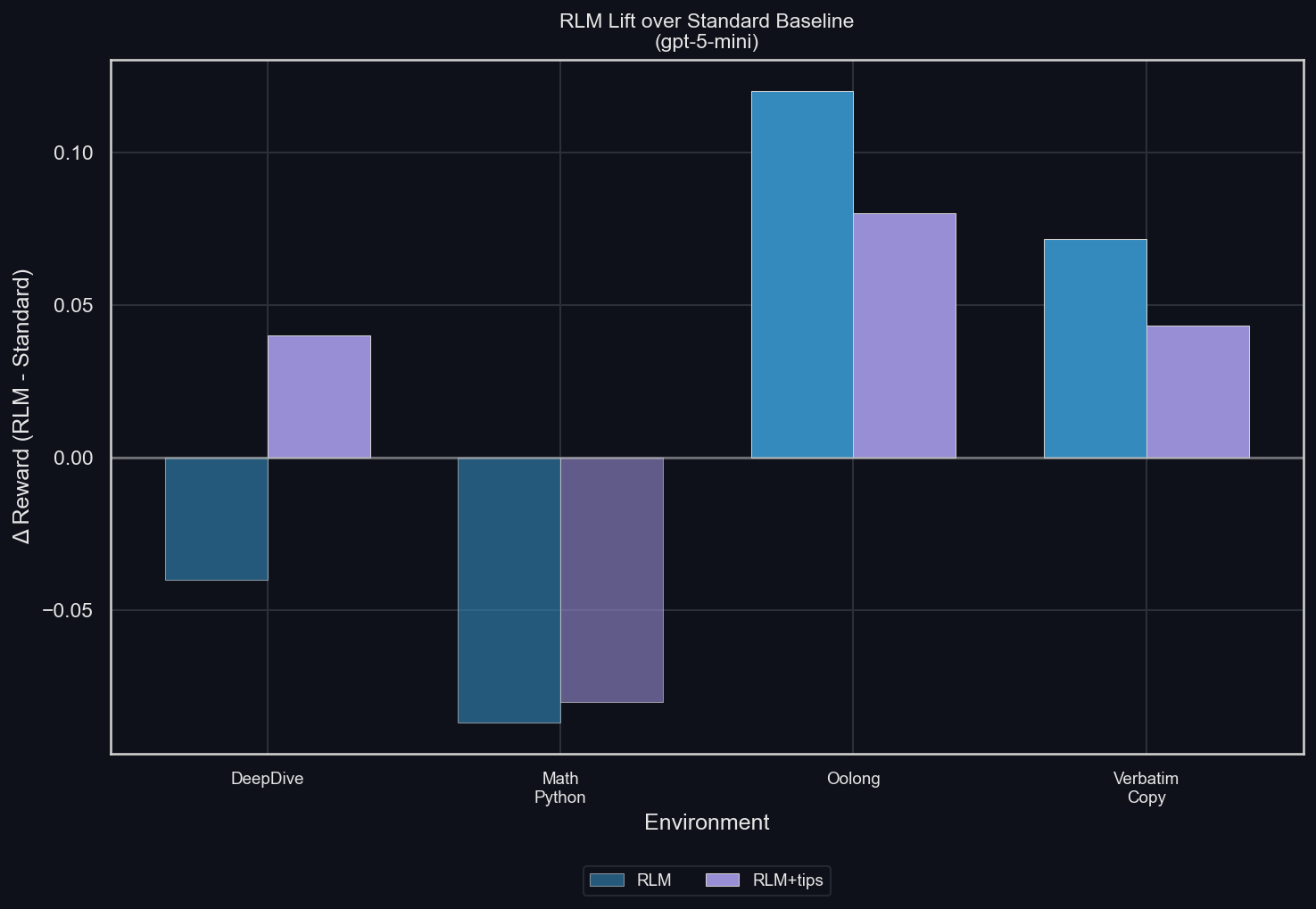

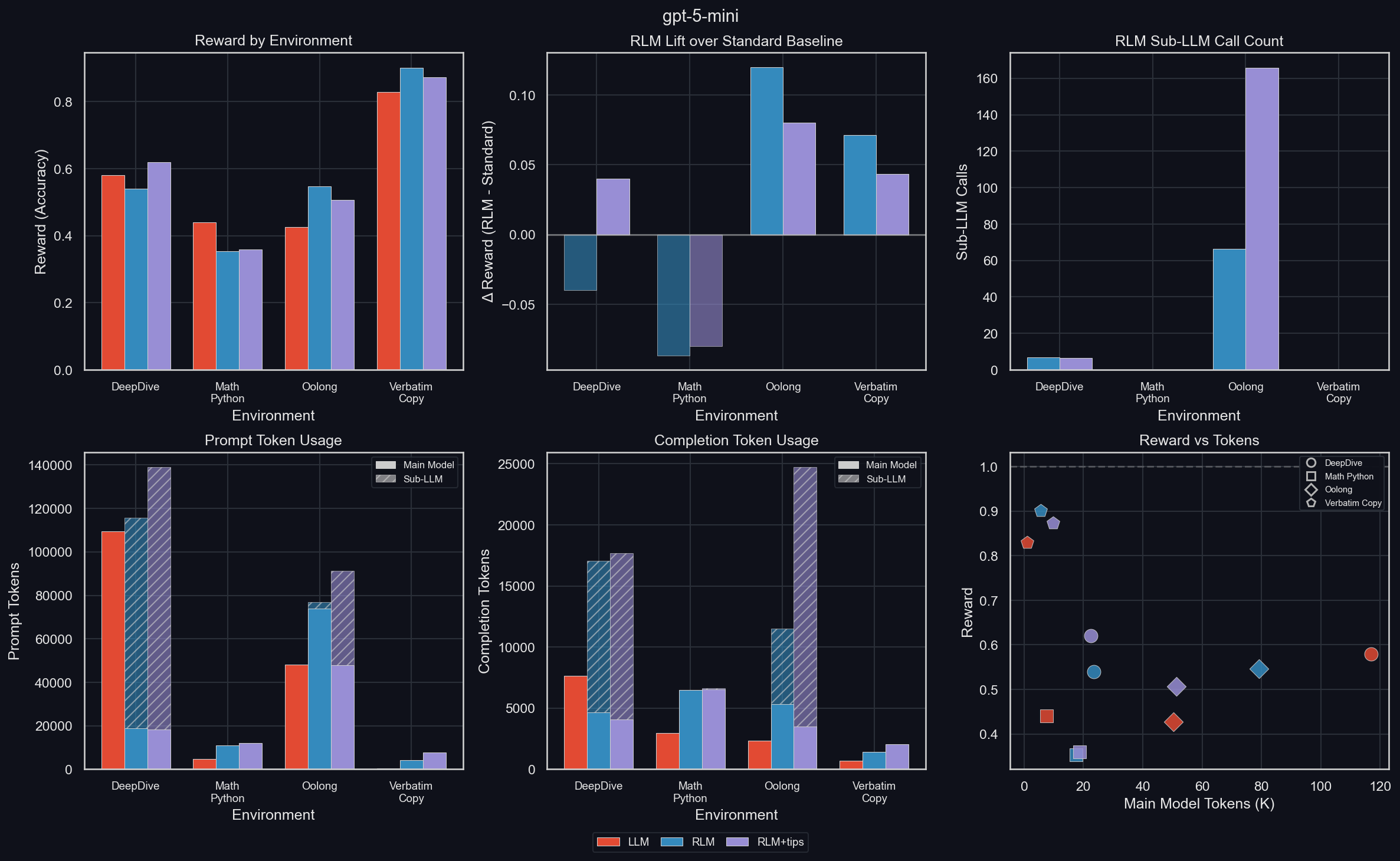

Mean reward by environment & RLM Lift over Standard Baseline

The mean reward over 50 rollouts for the different environments (uv run environments/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I reward):

The lift in mean reward compared to the LLM (uv run environments/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I lift):

The RLM tends to increase final reward. The exceptions are two-fold:

For math-python, the reward is significantly lower with than without the RLM. Because the RLM allows for the exact same behavior for solving the environment as the LLM (which also has access to Python tools, with the same libraries pre-installed), this performance gap is evidence for overfitting to the benchmark using a standard Python tool. We suspect that a model that is properly trained in using the RLM will be able to at least match the performance of one without the RLM.

For DeepDive, the RLM is worse than the LLM, except when it is told a strategy for solving Deep Research problems: split the question up into multiple, smaller research problems, and let sub-LLMs solve them, then iterate until complete. This is evidence to us that a lot of performance is being left untapped due to poor usage of the scaffolding. Again, this will be solved by training.

Overall, these results give us confidence that the RLM scaffolding can, with training, improve model performance significantly.

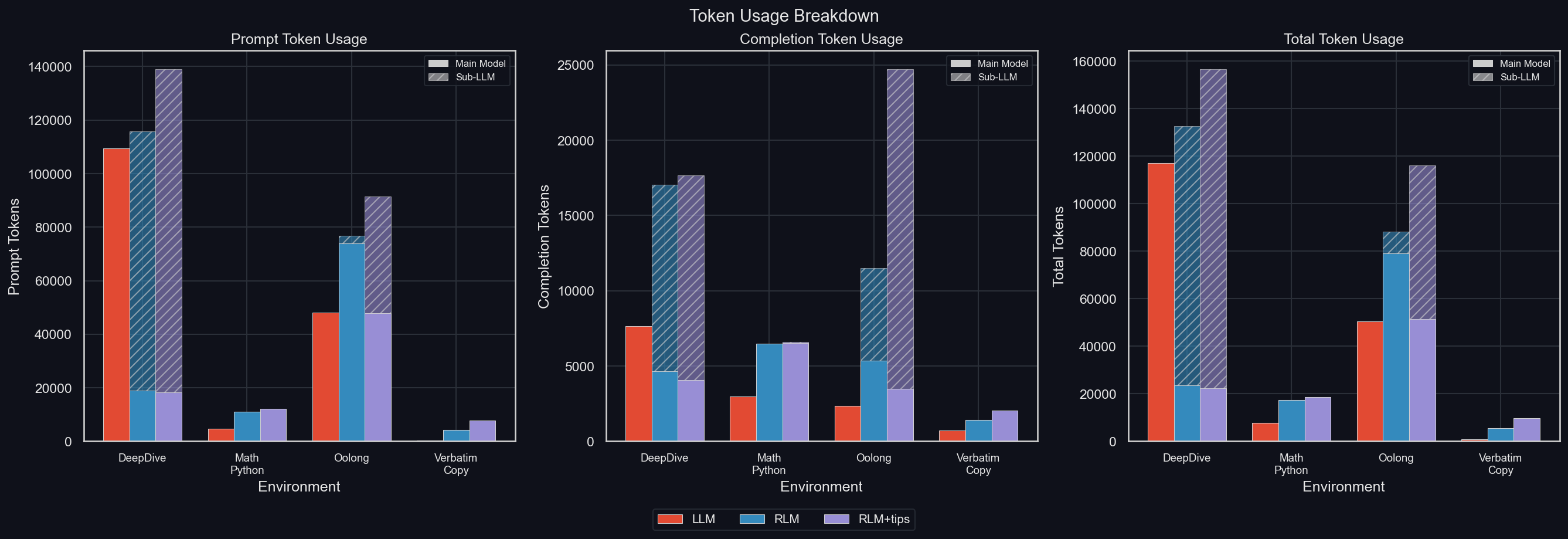

Token Usage

uv run environments/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I tokens_breakdown

In DeepDive and Oolong, the RLM uses a significant amount of sub-LLM tokens, and the proportion of completion tokens to prompt tokens is much higher in the sub-LLM calls than in the main model (for either LLM and RLM). This points to sub-LLMs enabling a scaling of thinking-tokens at a much lower main model context length.

And the main model context length is much lower when using sub-LLMs: in DeepDive, this is immediately apparent, but it's true even in Oolong. The reason why this isn't clearly visible for Oolong is that for the LLM, the API rejects long Oolong inputs, because they exceed the context window. Those are thus counted as having used no tokens. We will see this in more detail later.

For math-python, the RLM with tips performed a single sub-LLM call in a single rollout; however, that has no visible effect on the token production and thus, GPT-5-mini can be said to use no sub-LLMs for math-python.

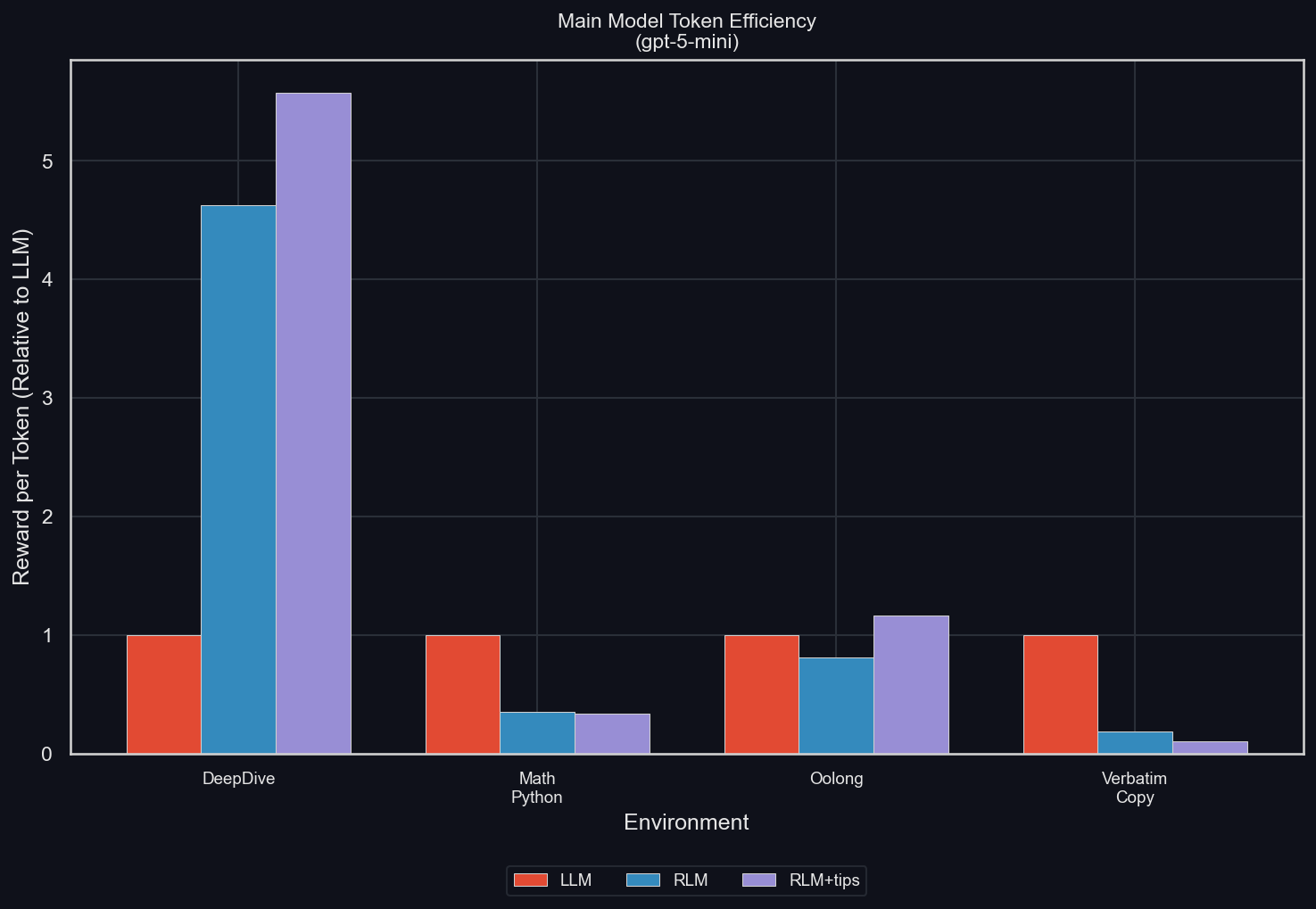

Main Model Token Efficiency

The Main Model Token Efficiency is the average reward divided by the average number of tokens in the main model's trajectories (Note: for the standard LLM, the main model trajectory is the full rollout, but for the RLM, it doesn't include sub-LLM calls). We normalize it against the efficiency of the LLM, in order to make the values comparable between the different environments. These are the results (uv run environments/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I efficiency)

The RLM increases it significantly for DeepDive, where most tokens are handled by sub-LLMs, which don't count toward the main model token count

Oolong should show a significant increase in token efficiency for the RLM compared to the LLM, because it's another very long-context environment where the RLM only ever gets access to the data via the Python REPL. The mixed results come from the aforementioned API rejections of long Oolong prompts. Since the longer problems are harder, but are only seen by the RLM, the LLM has an advantage in this setting.

Both math-python and verbatim-copy are hurt significantly in token efficiency. Both contain the full prompt in the model's context, but the reasons for the different main model token efficiency are different between both:

- math-python causes the RLM to simply think inefficiently and poorly, which explains the decreased performance at increased main model token count

- verbatim-copy is improved by the RLM, but the solution strategy is very different between LLM and RLM: the LLM simply one-shots the answer, while the RLM has to call a tool to give its response, and often does so repeatedly to slowly improve its answer

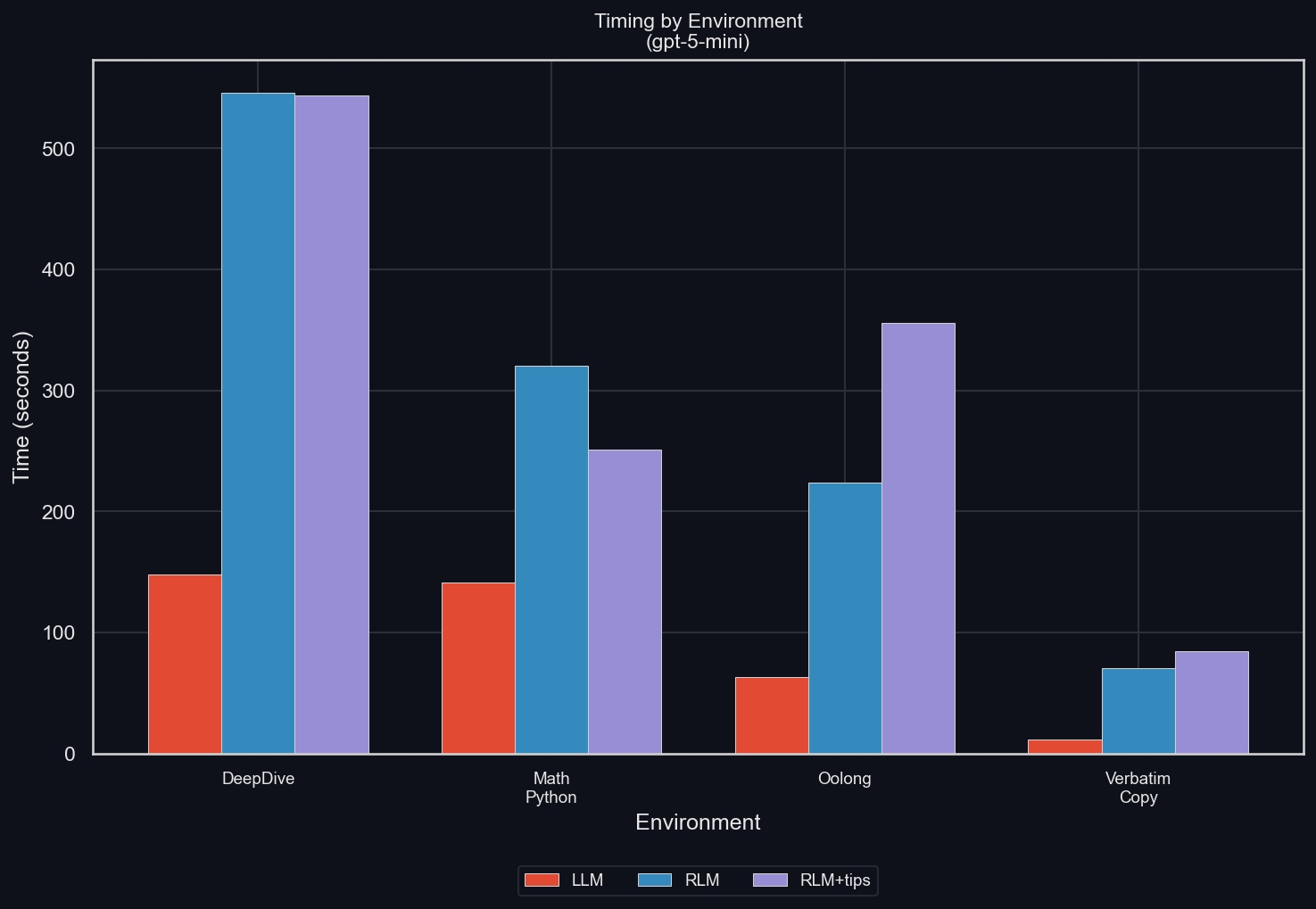

Timing by Environment

uv run environments/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I timing

In all cases, the RLM increases the time required to finish the job significantly. However, the reasons for this differ between the environments:

- For DeepDive and Oolong, it's due to an increased total token budget, paid mostly by sub-LLMs. While those can be parallelized, GPT-5-mini doesn't always do so (pointing to further potential efficiency gains from training), and even where it does, the API can be limiting, and the increased total token budget has to be paid. Most importantly, though, using sub-LLMs leads to a strong increase in completion tokens

- For math-python, it's simply the increased amount of (inefficient) thinking that the main RLM performs

- For Needle in Haystack, the total number of tokens is reduced a lot for the RLM (and there are no sub-LLM calls). However, the LLM can simply spit out its answer in a single token. The RLM is writing code to solve its problem, and then again to provide its final answer. That means that in this environment, the LLM's token are almost all spent on pre-filling, while the RLM's are in large part spent on decoding

- For verbatim-copy, the cause is the increased amount of tool-calls and turns we've discussed above

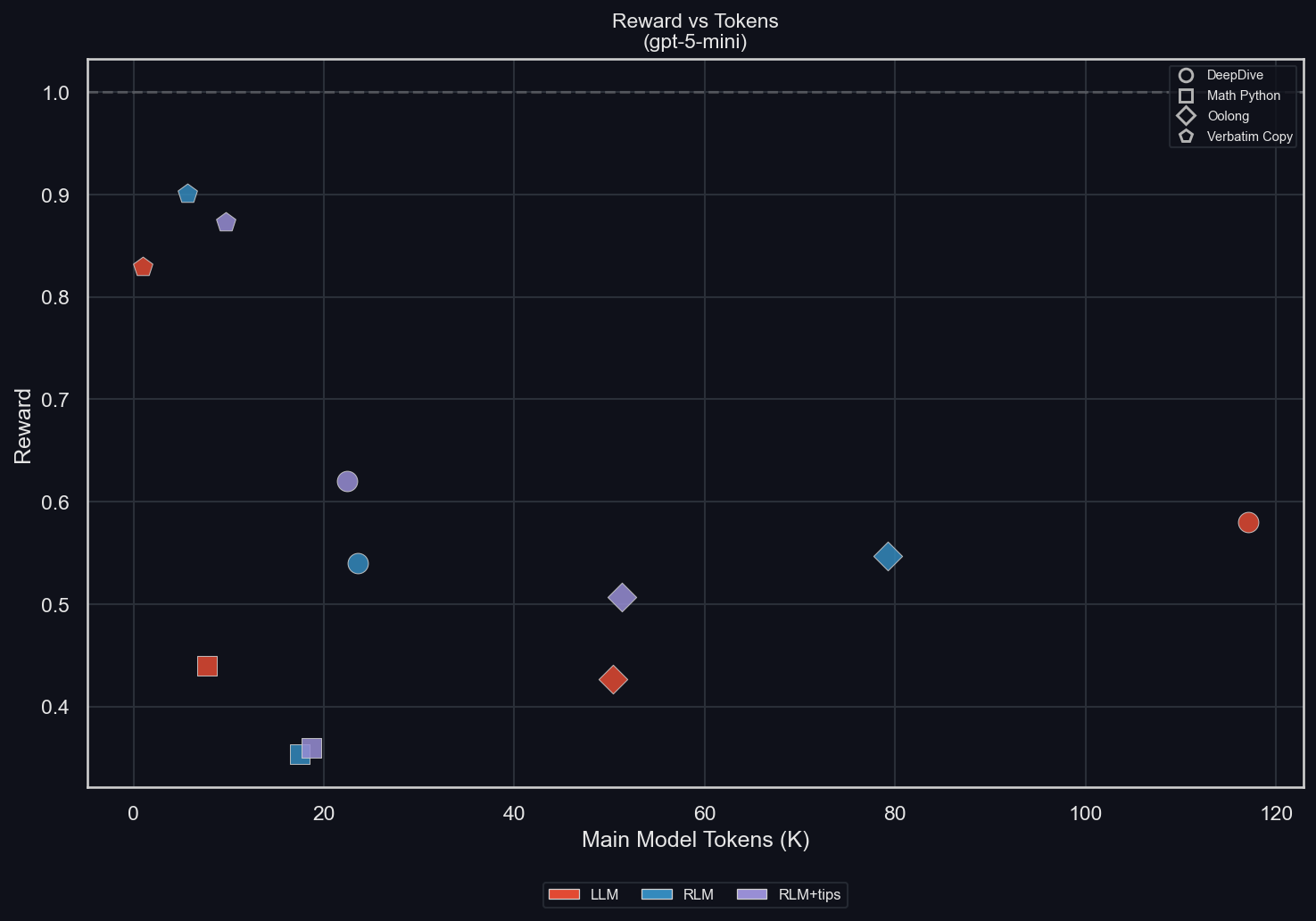

Reward vs Tokens

uv run environments/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I scatter

We can see for each environment (differentiated by shapes) how the mode (LLM, RLM, RLM+tips; differentiated by colors) affects both the main model tokens and the reward.

- DeepDive: we can see how strongly the context window of the RLM is compressed, while retaining performance

- math-python: the presence of the RLM harness, despite enabling the exact same behavior as the default LLM harness, clearly makes the model dumber and less efficient at this task

- Oolong: the RLM improves performance. With tips, it retains the main model context length, but without them, the main model context length is increased a lot (again, we will see that this is a function of only the RLM ever actually seeing the longest problems)

- Verbatim copy: The RLM improves performance in line with its increased token usage

Across-environment results: Summary

These results generally make us confident of the usefulness of the RLM for both reducing the main model's sequence length to allow for longer coherent work, while at the same time improving its performance by scaling sub-LLMs, using Python to perform work, and improving its answer iteratively.

It also makes us confident that training will bring out significant further performance improvements.

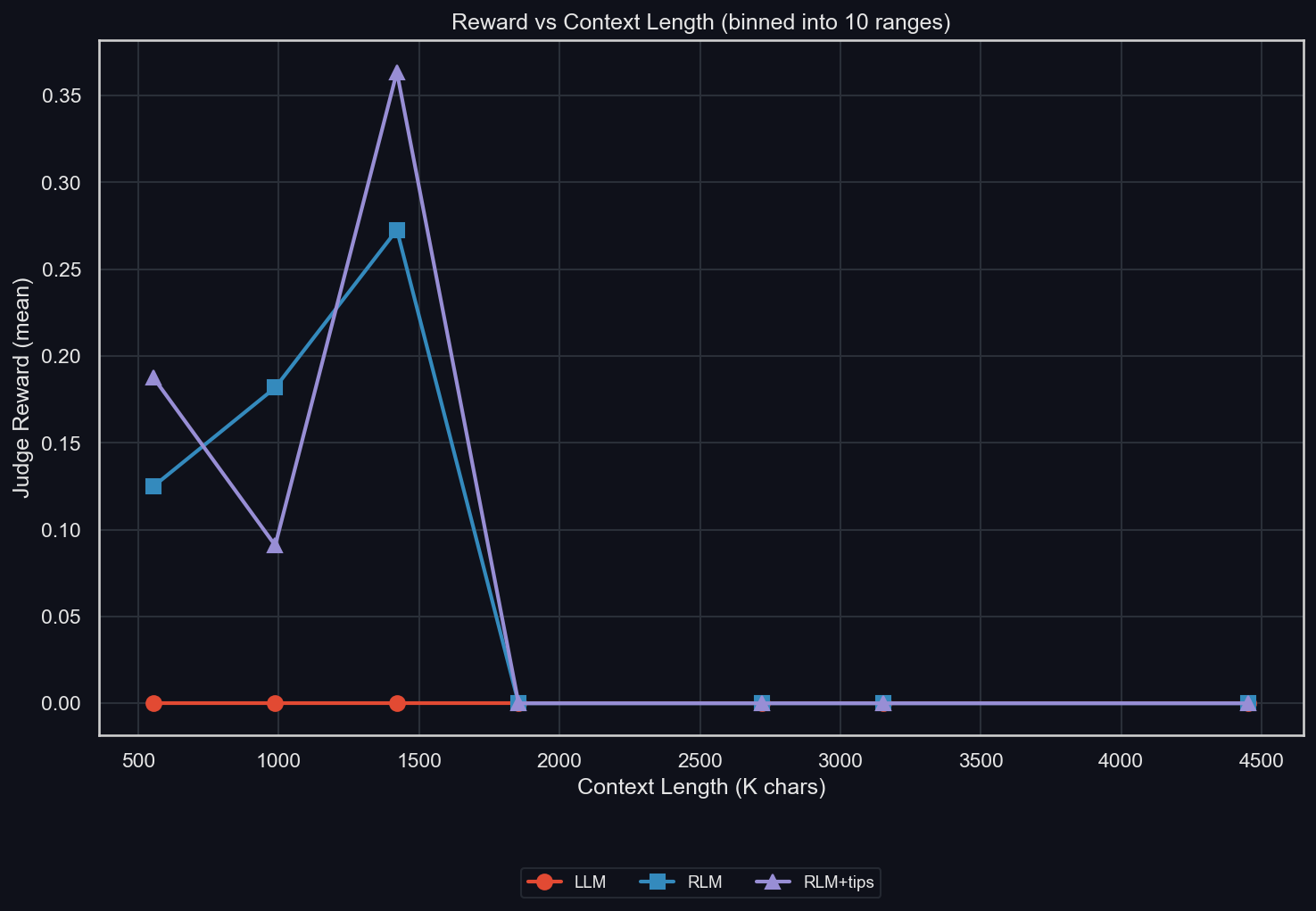

The TL;DR is this plot (uv run environments/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini):

Results per environment

Some of the environments have settings which we ablated in addition to the default settings shown above. These show interesting, data-dependent behavior.

math-python

To test the idea of using sub-LLMs in math-python mentioned above, we added a secondary environment tips prompt:

_ENV_TIPS_SUB_LLMS = """

<env_tips>

Use `llm_batch()` for reasoning steps: breaking down the problem, validating intermediate results, and checking your logic. Use Python for numerical calculations.

</env_tips>"""

Then, we run the same ablations as before (with the same random seed leading to the same data order), but vary the timeout of each of the LLM's commands: 120 seconds (the default used for all other experiments), 300 seconds, and 600 seconds.

The theory was that the increased time allows the model to use sub-LLMs more generously. And importantly, the model is always told what the per-command timeout is, and how long any given call to the REPL took, so it could theoretically figure out to use more parallel sub-LLM calls when the timeout is longer.

As before, each setting is tested on the same 50 prompts.

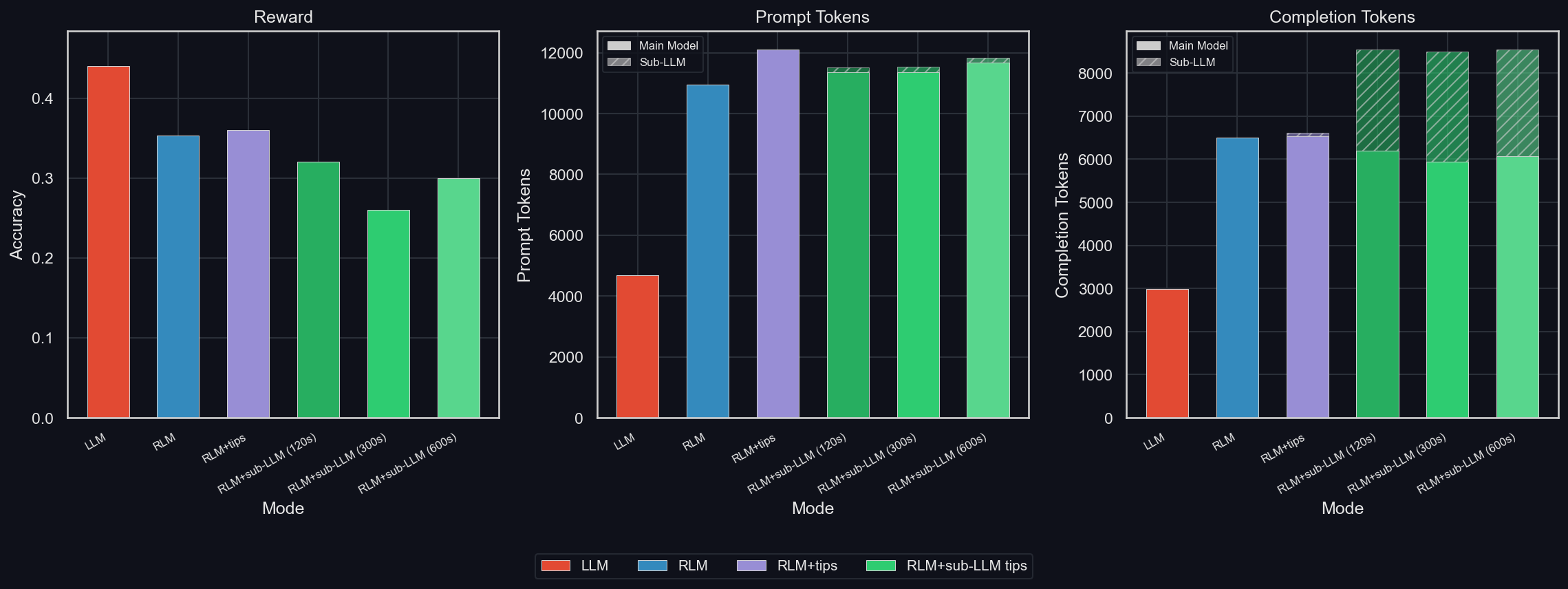

Below, we plot the most important statistics about these ablations:

uv run environments/math_python/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I ablation

We quickly see three results:

- Using sub-LLMs for math makes GPT-5-mini weaker

- It barely reduced main model token usage (it's still way higher than for the LLM)

- It adds sub-LLM tokens, but only a little, because the GPT-5-mini RLM seems to use sub-LLMs very sparsely even with the extra prompt

- The RLM gives very little context to the sub-LLMs: they consist mostly of completion tokens, with very little prompting involved, which points to improvements being possible

It remains to be seen if training a model to use the RLM scaffold and use sub-LLM calls extensively will help with these statistics. If yes, then the problem is likely just a lack of training for this specific setup. If no, it's possible that math is simply not a domain that benefits strongly from a multi-agent system.

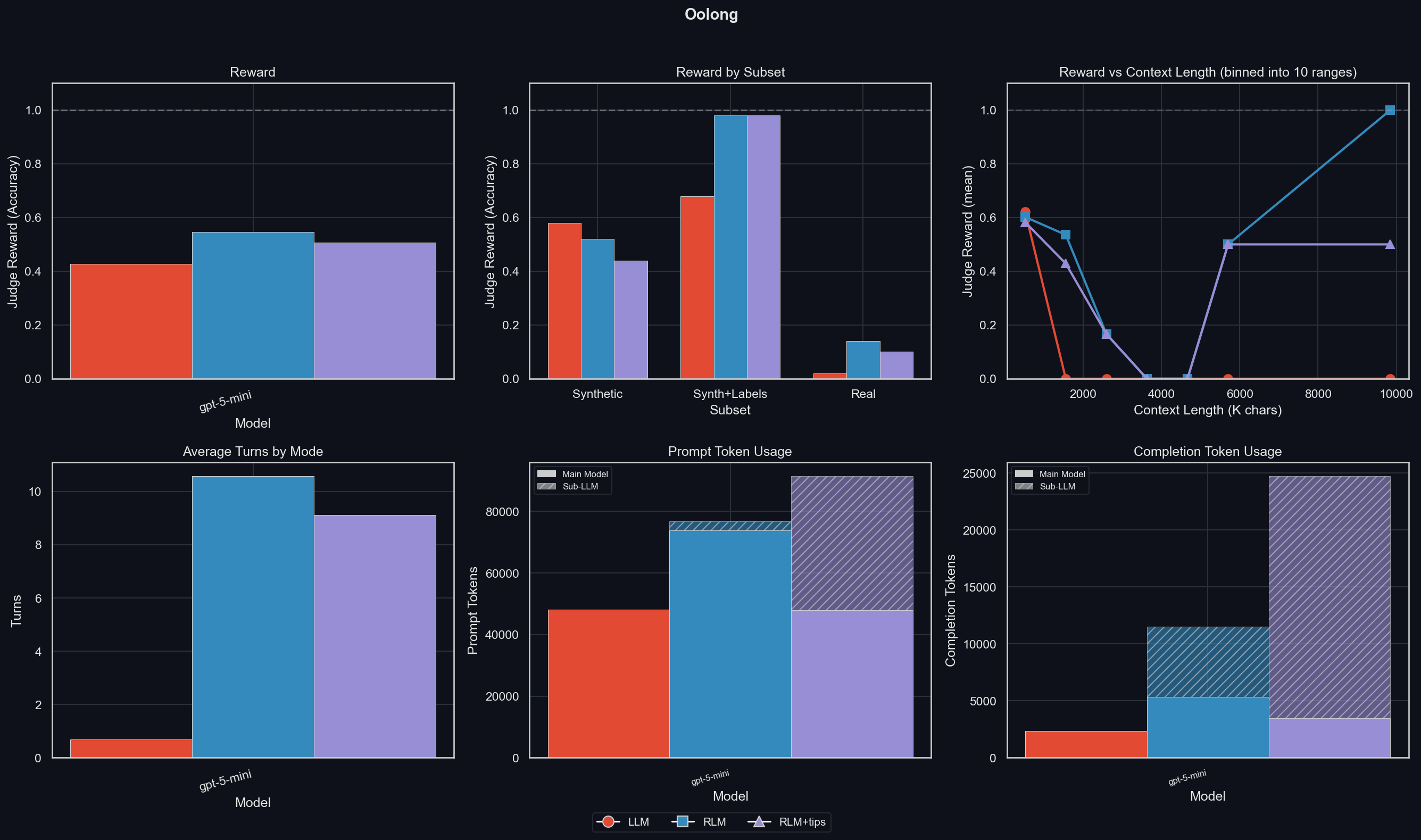

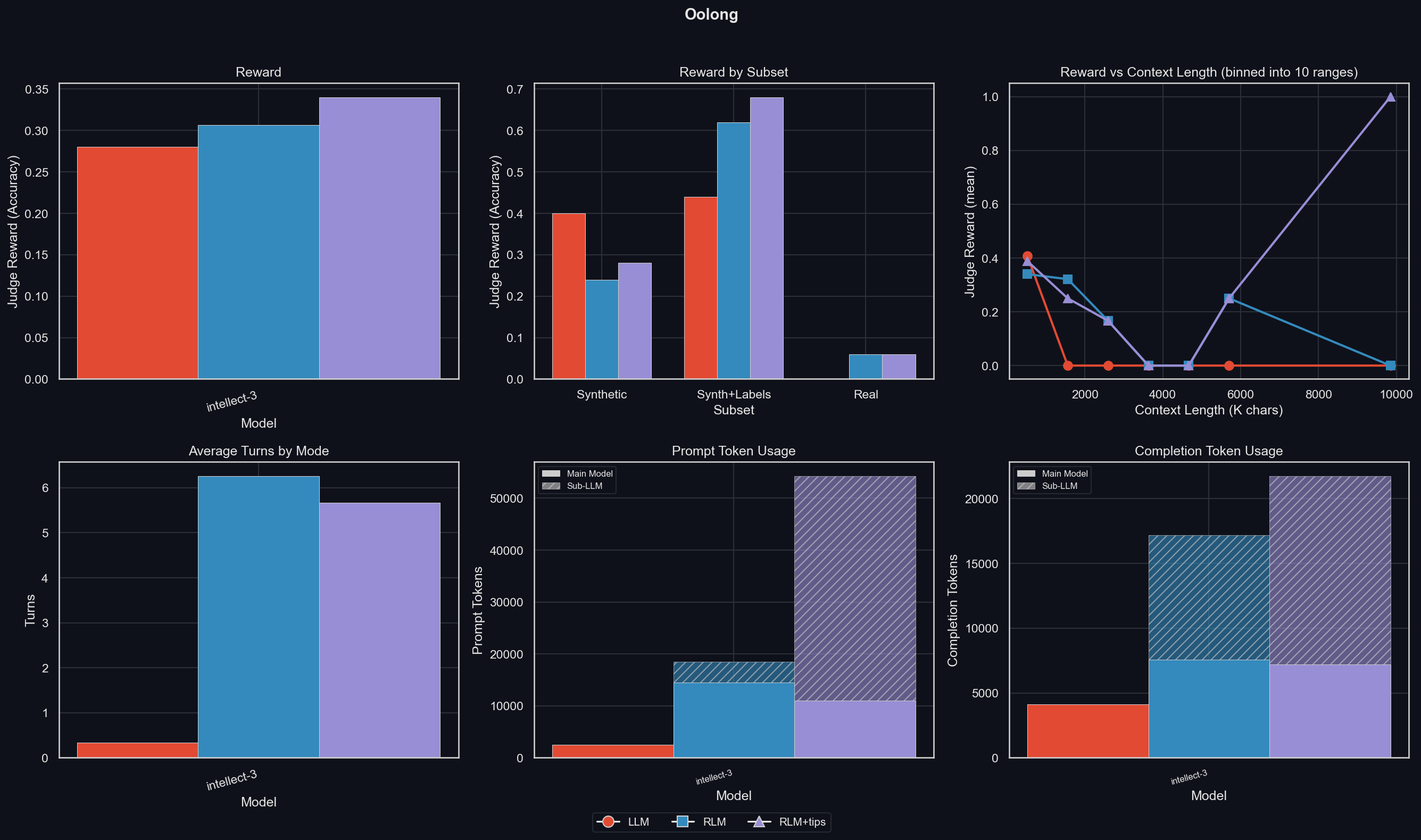

Oolong

uv run environments/oolong/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -a

We've already seen that the reward is increased by using the RLM.

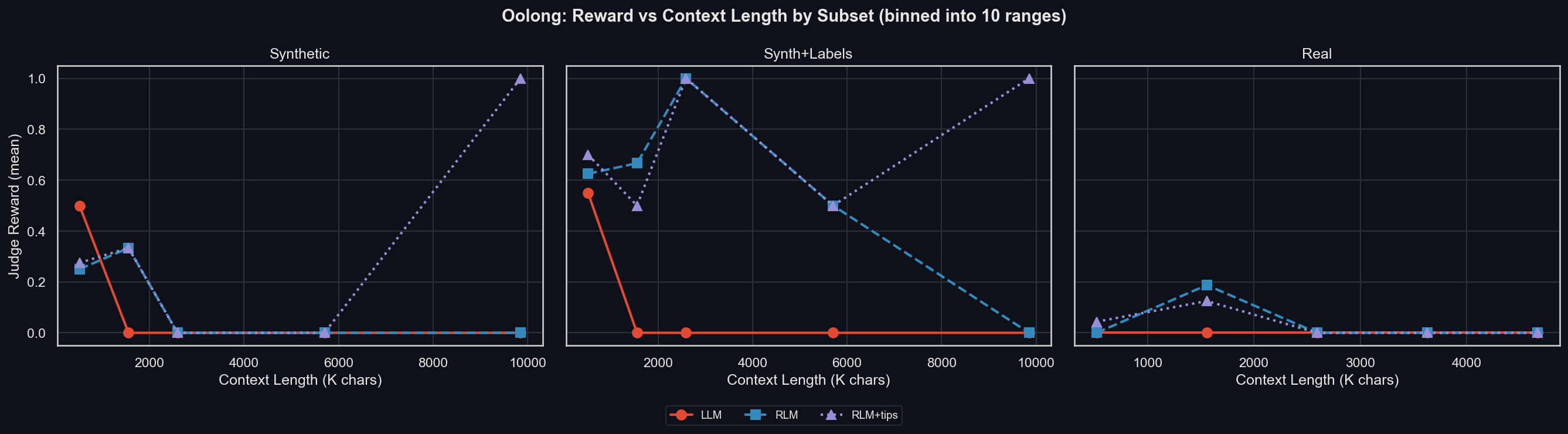

This plot also shows Reward by Subset. This is interesting because it shows a big difference between RLM performance depending on the data type:

- For synthetic data with labels, the RLM outperforms the LLM easily

- For synthetic Oolong data, RLM is worse than the LLM, and more so when given the tip to heavily rely on sub-LLMs

- However, for real data (which is the most complex and most important), the RLM outperforms the LLM by a large margin, which demonstrates that the reliance on sub-LLMs is useful for complex data

We can also look at the Reward vs Context Length subplot. Context length here refers only to the length of the input data, which is fully inside the LLM's context but only available from within a Python variable for the RLM. This shows a strength of the RLM: the LLM is better than any RLM only for the shortest-context data available.

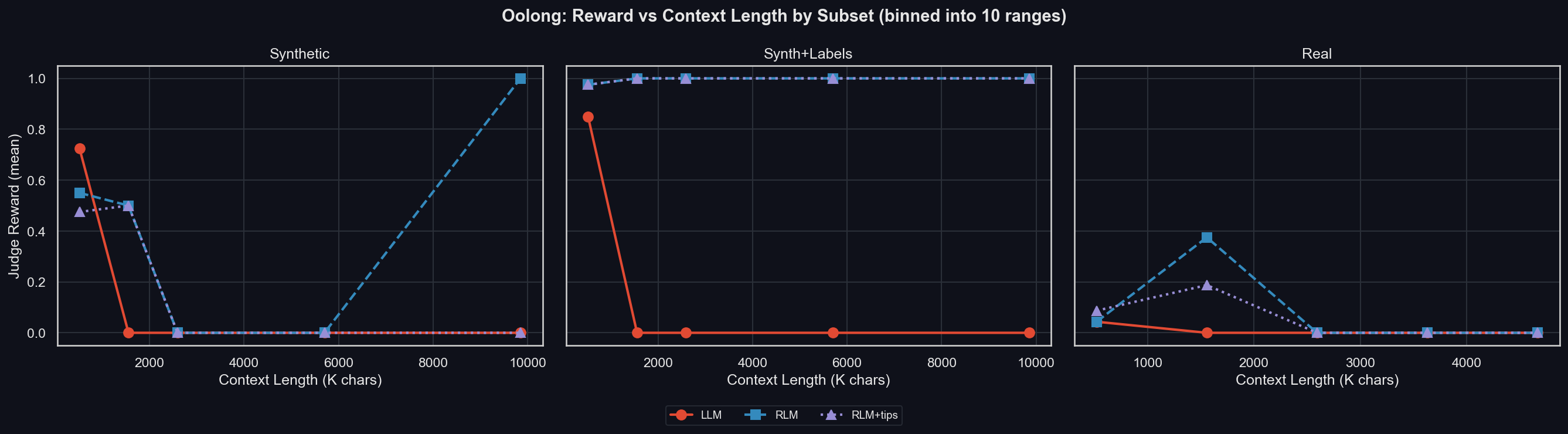

What's less clear is what causes the dip in accuracy in the middle context-lengths. Let's look at the same sub-plot, but per subset (uv run environments/oolong/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I context_binned_by_subset):

We can see that the dip originates from missing samples from Synth+Labels in those bins, and a weird performance spike at the longest context lengths for the RLM. For the most important, real data, the RLM is significantly better than the LLM at a context length of around 1.5M characters (~300-400k tokens). Beyond that, no model can succeed.

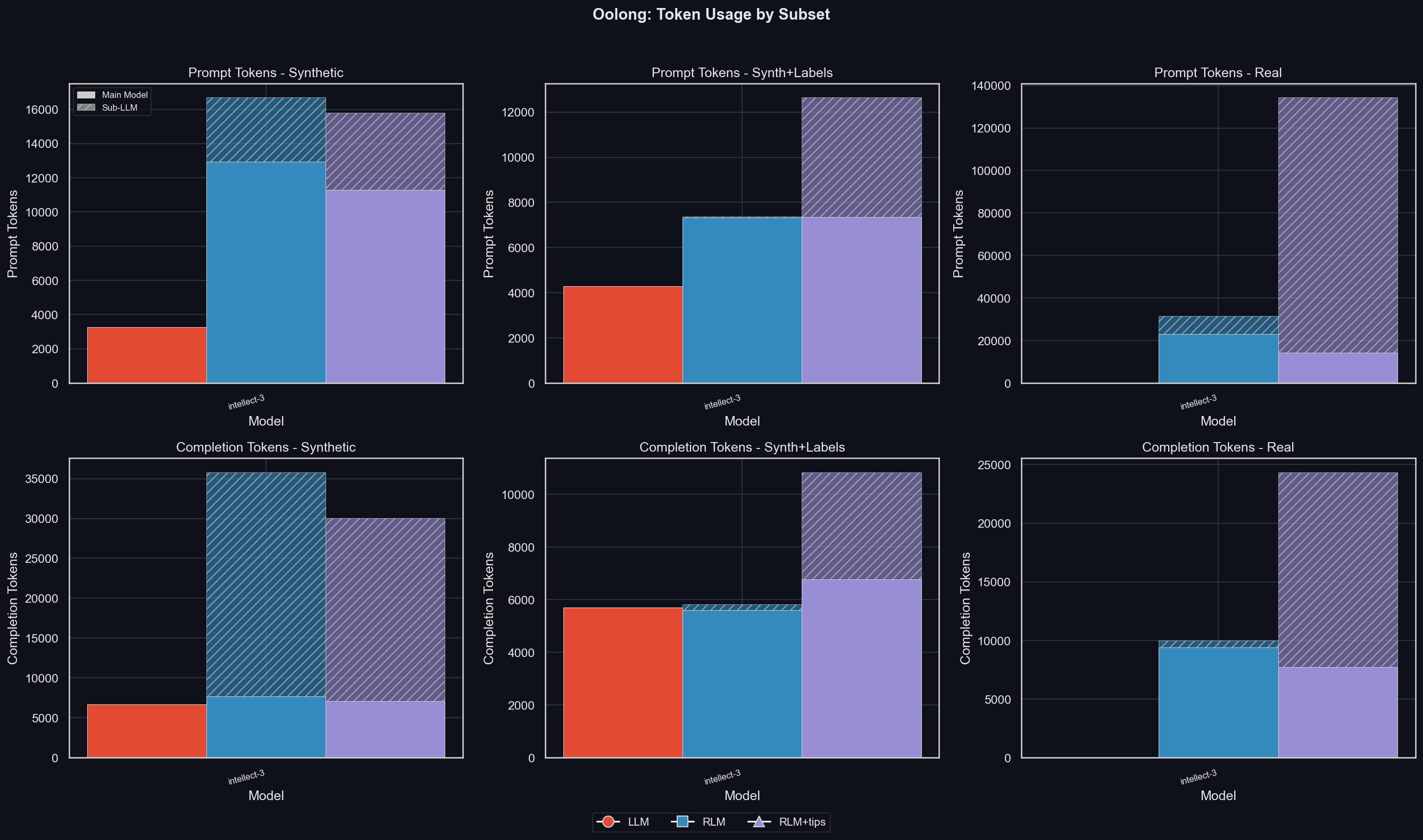

Finally, the Prompt Token Usage and Completion Token Usage shows that the RLM uses more tokens than the LLM. Giving it tips on how to solve Oolong makes it put fewer of the prompt tokens into its own context window, and instead makes it put more of those into the sub-LLMs, which might explain the slightly reduced performance of the RLM+tips compared to the RLM. The sub-LLMs also produce far more completion tokens when the RLM is given tips.

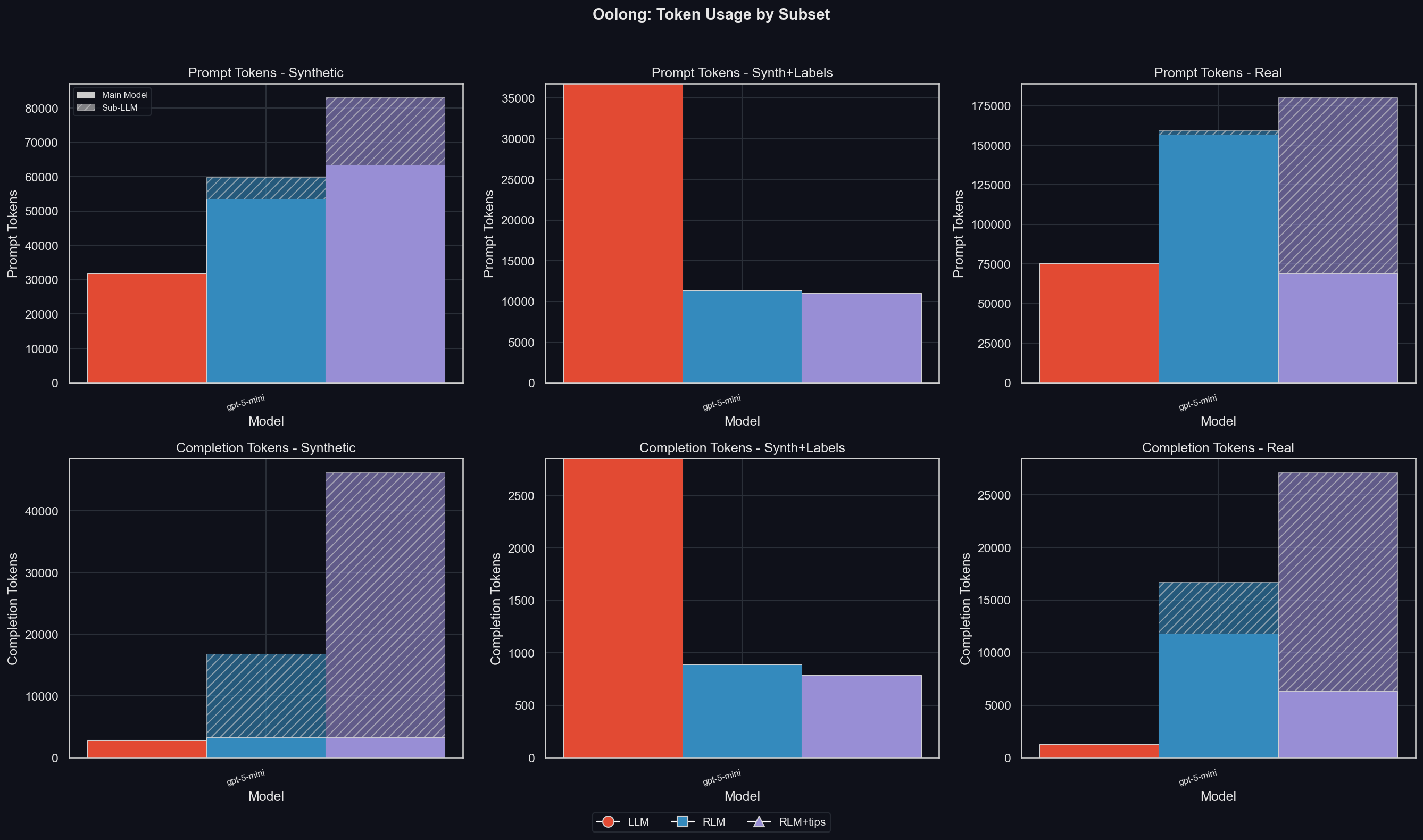

To get a sense for the strategies pursued by the RLM for the different subsets, here are the average tokens per subset (top row: prompt tokens, bottom row: completion tokens; uv run environments/oolong/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I tokens_by_subset):

We can see that for the synth dataset, the RLM uses a significant number of prompt tokens, especially when given tips; and almost all completion tokens are by the sub-LLMs. Of course, we already saw that the increased token-usage compared to the LLM comes from the later simply not consuming or producing any tokens for any but the shortest of contexts in the synth split.

For synth with lables, the RLM never used any sub-LLM calls. Instead, it solved its problems with regular expressions, which also leads to the perfect scores at any context length.

Finally, the RLM uses far more tokens for the real subset. The RLM+tips manages to keep the main model token usage comparatively lower than the RLM without tips, but it uses more tokens via sub-LLMs.

Verbatim-copy

For verbatim-copy, there are three interesting plots in addition to the results seen before.

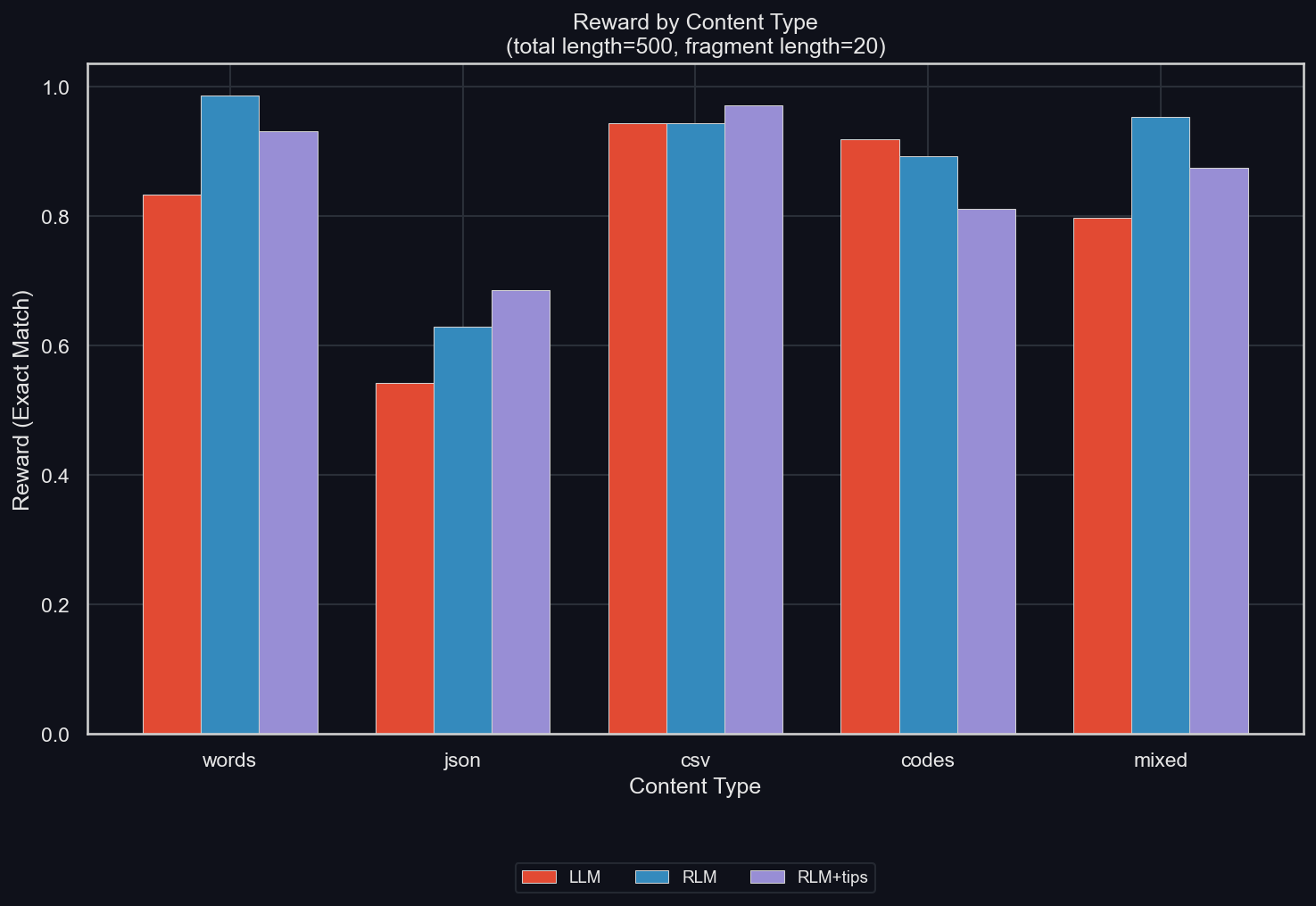

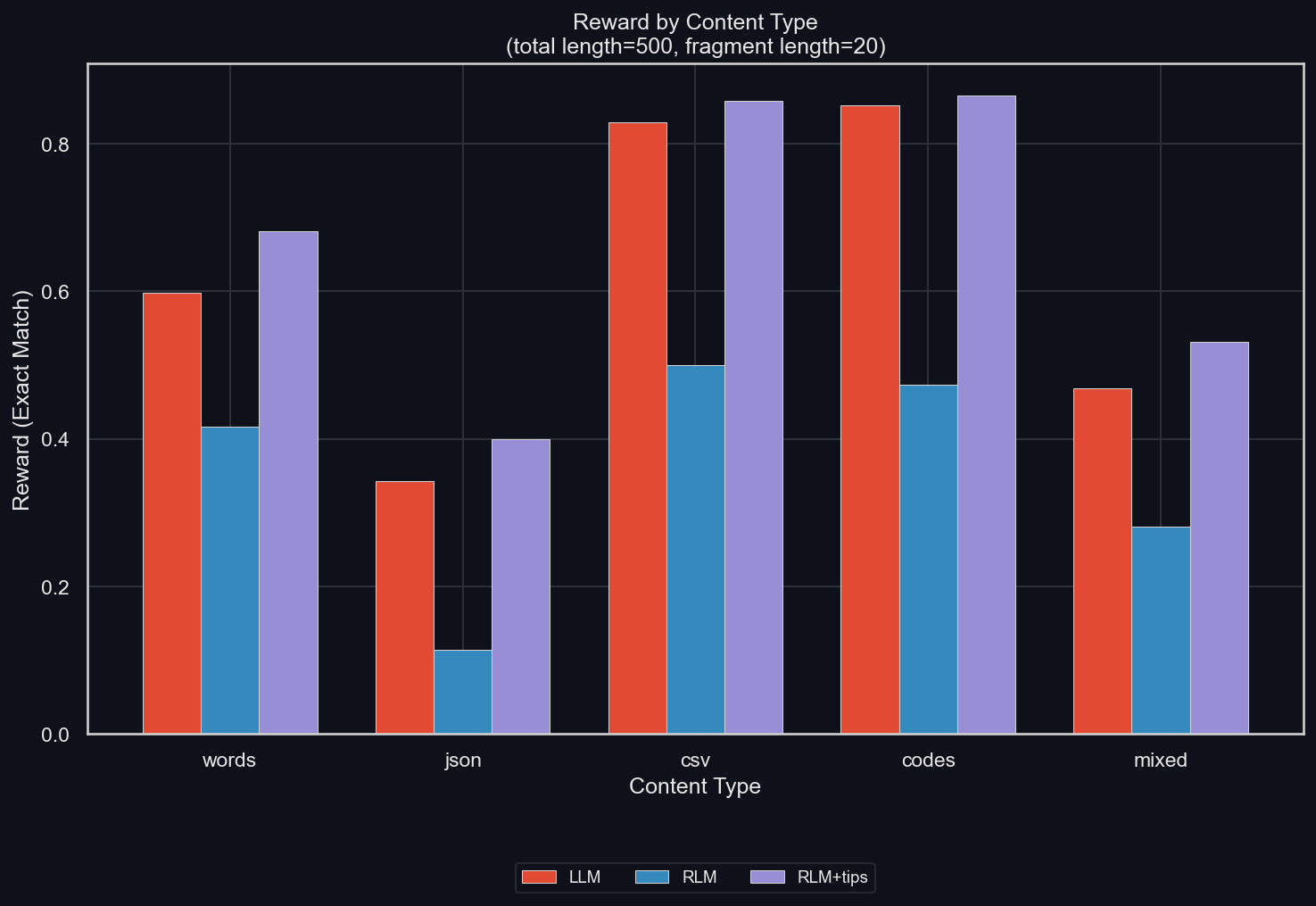

Reward by Content Type

We ablate the content type, which was "all" (meaning a random mixture of the below types) (uv run environments/verbatim_copy/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I reward_by_content_type):

The JSON data is clearly the most difficult, and most helped by the RLM. This goes against the argument brought up before: that the RLM's problem is with escape characters in tool-calls. That's because those must be used the most with JSON data.

In fact, the RLM is better than the LLM for all content types except for codes (which are many UUID codes put together). I don't know if this exception is random or not; but at a sample size of 50 per mode and content type, it seems likely.

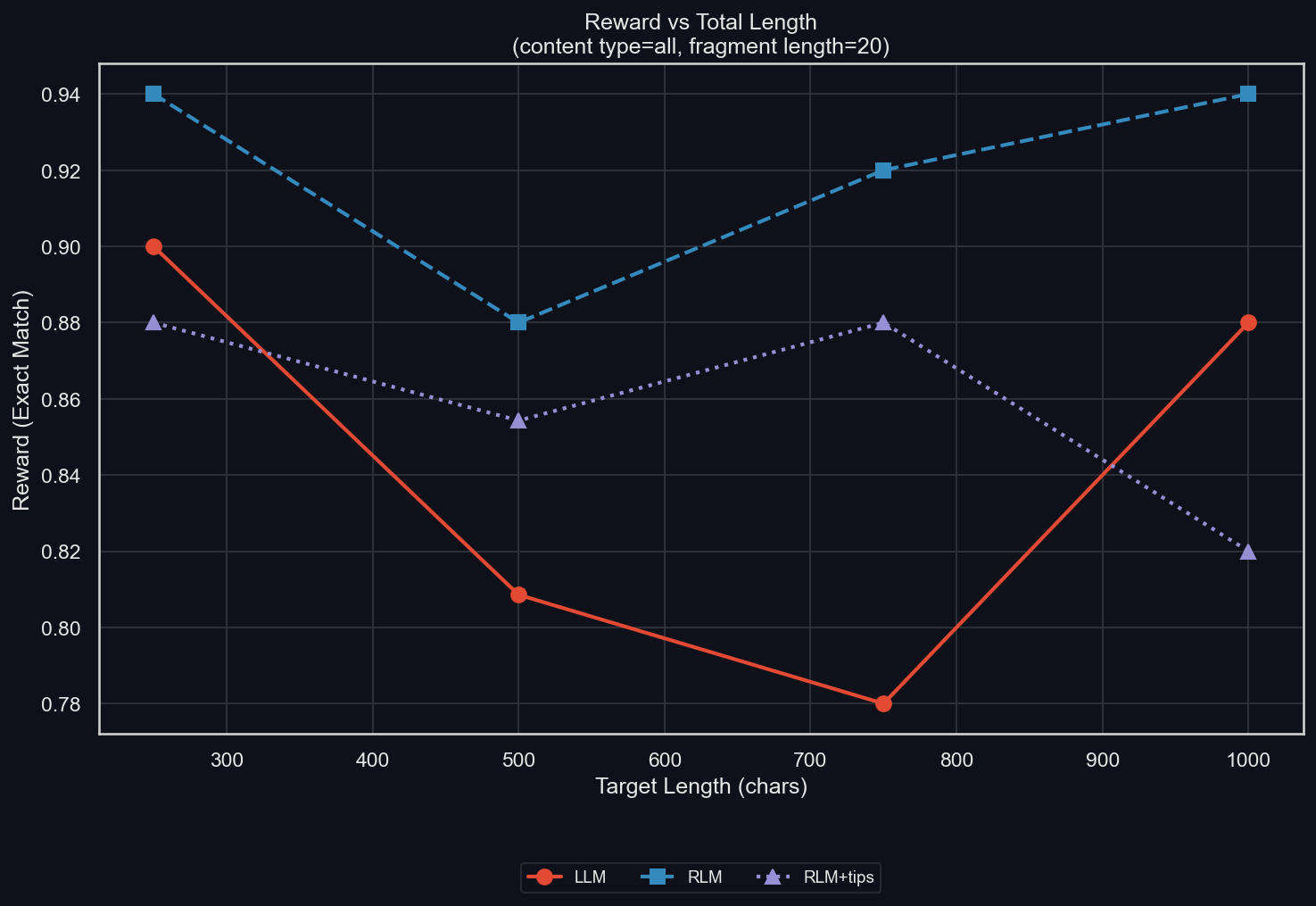

Reward by content length

We ablate the total length of the produced content (uv run environments/verbatim_copy/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I length):

The trend is that longer data leads to lower reward, though the slope is shallow and the datapoints are noisy. The RLM strictly dominates the LLM, while the RLM+tips is better than the LLM except for very short and very long data (though that it's these specific lengths is almost certainly random).

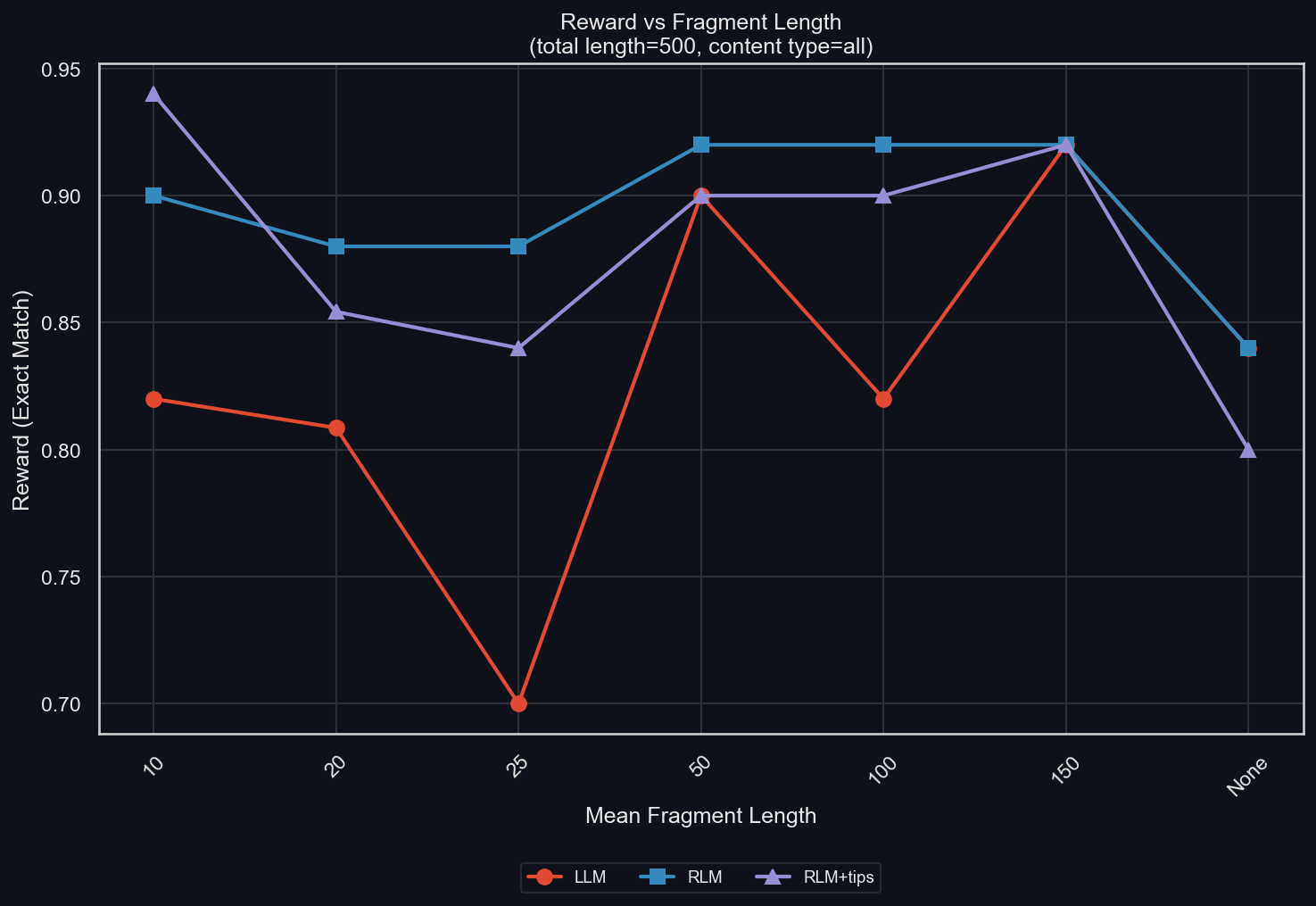

Reward vs Fragment Length

We also ablate the fragment length (uv run environments/verbatim_copy/plot_results.py -m gpt-5-mini -I fragmentation):

Remember that we cut the data into small pieces of mean size fragment length, and cut those together randomly. The size of the pieces varies though (except for "None", which means no fragmentation), and we oversample and take pieces from different settings (in the "all" setting we show here that can mean splicing together samples of different content types).

What this plot shows is that there is no clear relationship between fragment length and reward; this modification seems to not make a big difference; at least not for the RLM! For the standard LLM, finer fragmentation tends to lead to worse results, increasing the performance difference between it and the RLM.

Results for other models

While GPT-5-mini was the best user of the RLM in our experiments, we also ran ablations with other models. Specifically, we were interested in the capabilities of Open Source models, which will become more important as we move on to SFT data generation.

DISCLAIMER: we must stress again that this is not a measurement of any model's absolute performance on any benchmark. Again, we put no effort into optimizing the models' benchmark scores by hyperparameter tuning, and only care about the relative performance between LLM, RLM, and RLM+tips.

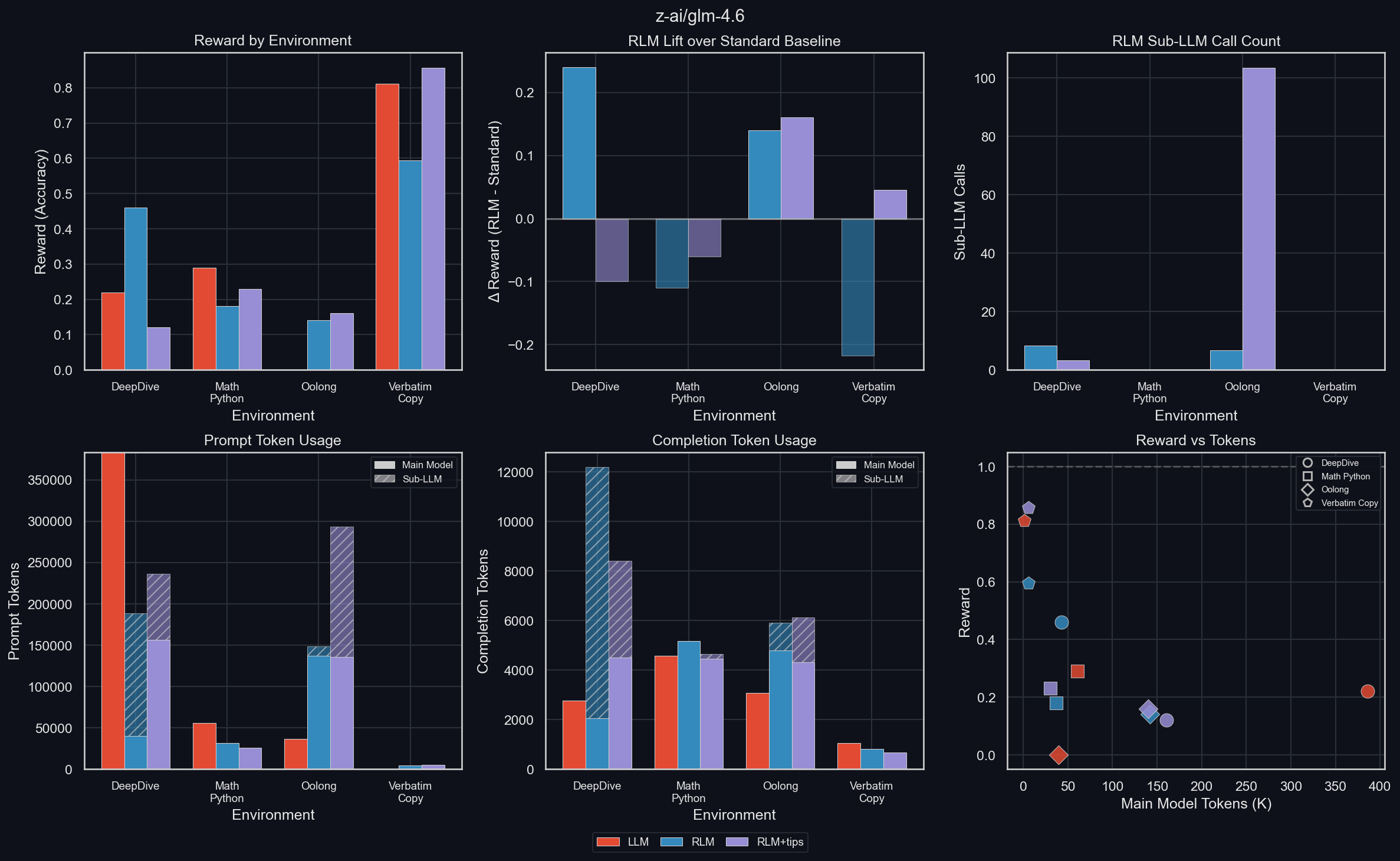

GLM 4.6

uv run environments/plot_results.py -m z-ai/glm-4.6

In DeepDive, the RLM gives the model an enormous boost in performance (almost a doubling), and an even stronger boost in main model token efficiency, pointing to a nicely compact context window for the RLM. This compaction is also shown in the Reward vs Tokens plot. However, when we give the RLM the same tips which slightly helped with GPT-5-mini, its performance crashes to just above half that of the LLM. The main model token efficiency for the RLM+tips is still higher than for the LLM, but the culprit can be seen in the timing and sub-LLM call count plots: when told to make extensive use of sub-LLMs, GLM 4.6 stops to do exactly that.

For math-python, we can see that like with GPT-5-mini, the performance is reduced by the use of the RLM. However, as opposed to GPT-5-mini, GLM 4.6 doesn't achieve this by thinking for longer but dumber; instead, it simply thinks less, as seen in the Reward vs Tokens plot.

GLM 4.6 gets zero reward on Oolong as a standard LLM, but non-zero reward with the RLM scaffolding. Tips make it slightly better, but also use significantly more sub-LLM calls. Looking at this in more detail (uv run environments/oolong/plot_results.py -m z-ai/glm-4.6 -I context_binned):

The RLM gets decent rewards up to fairly long contexts of up to ~1.75M characters, but 0 beyond that. The LLM always gets zero reward. Note: this is on "real" data.

Verbatim copy suffers from the RLM scaffolding, except when GLM 4.6 is given tips for how to make use of it, in which case it increases reward slightly. For some reason, using the RLM reduces completion tokens in this dataset; most likely due to a reduced amount of reasoning (which is wasted on this environment anyway).

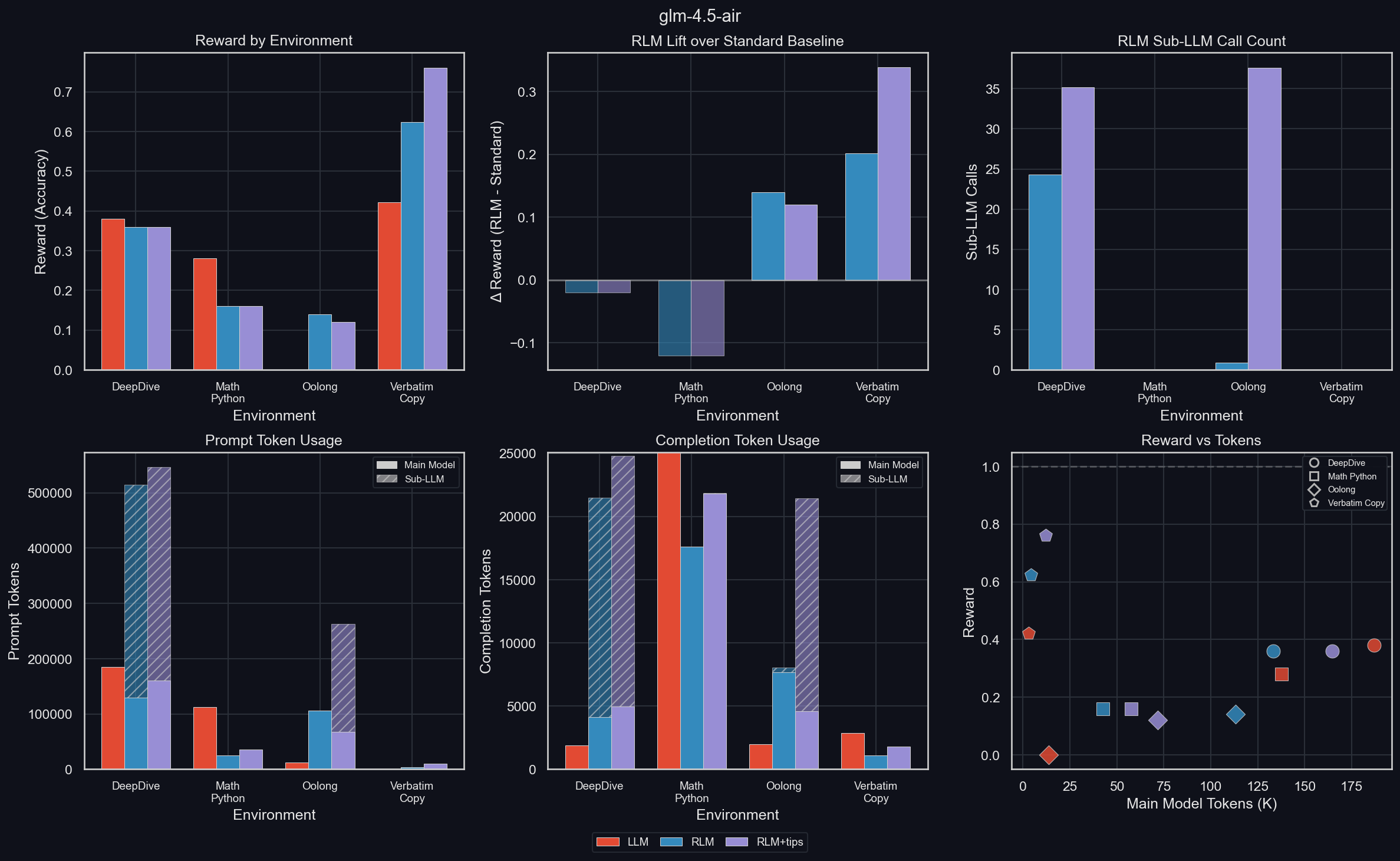

GLM 4.5 Air

uv run environments/plot_results.py -m glm-4.5-air

The results follow the general trends, except for DeepDive, where GLM 4.5 Air is weaker with than without the RLM, even though it makes a significant number of sub-LLM calls. This is another sign that training with the RLM scaffolding will unlock significant performance improvements.

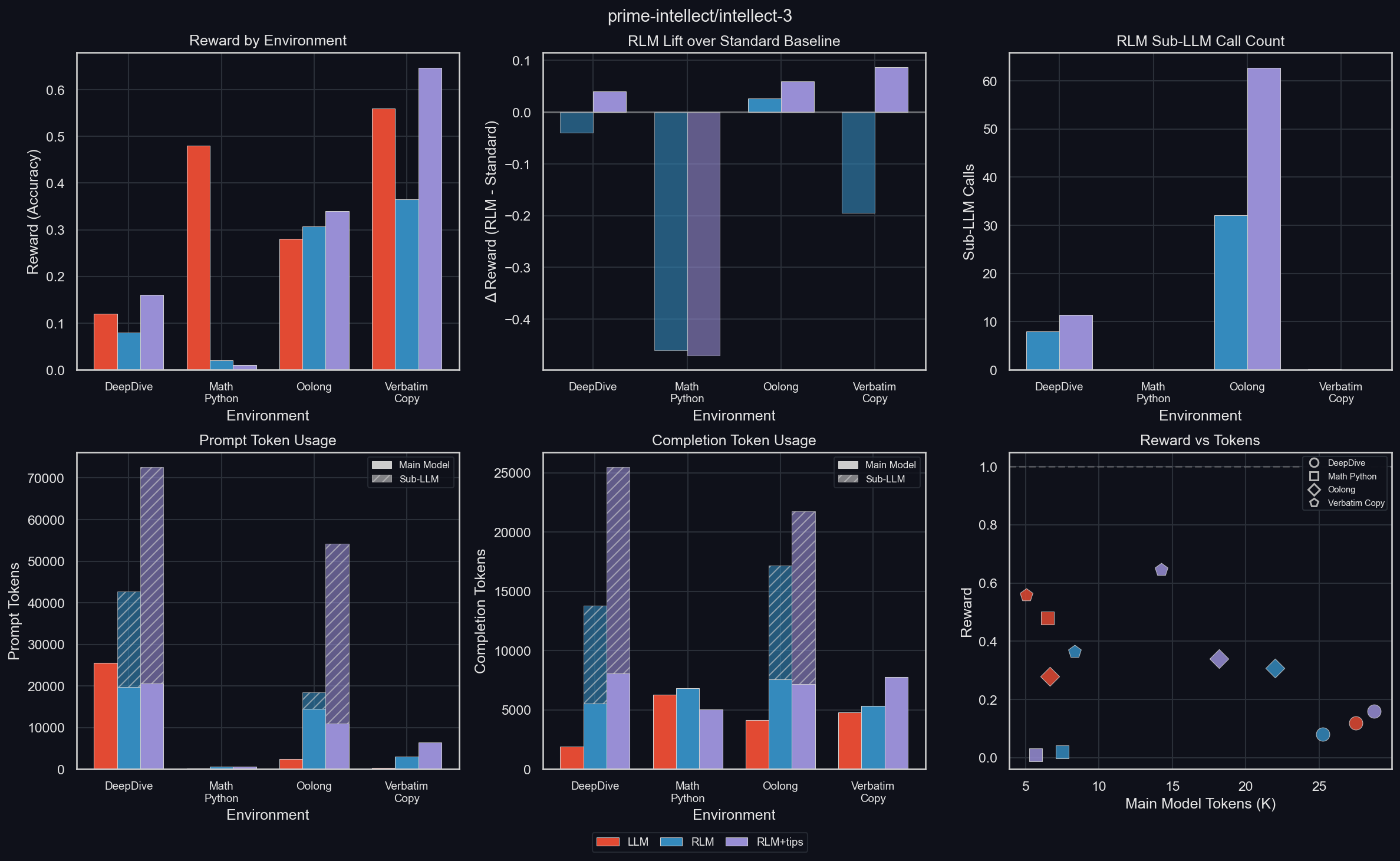

INTELLECT-3

uv run environments/plot_results.py -m prime-intellect/intellect-3

Our own INTELLECT-3 follows the same trends as the other models. It seems to benefit greatly from environment tips, and uses a large number of tokens (a similar number as GPT-5-mini, though for less average reward). For some reason, it is almost completely incapable of using the RLM in math-python, though it does so just fine in other environments.

Like with GPT-5-mini, we ran more thorough ablations with INTELLECT-3 on Oolong and verbatim-copy.

INTELLECT-3: Oolong

uv run environments/oolong/plot_results.py -m prime-intellect/intellect-3

Like with GPT-5-mini, the RLM performs better than the pure LLM, though INTELLECT-3 benefits from the tips. Like GPT-5-mini, the RLM performs worse on synth data, but better at the more important real data (and also the syth+labels data).

Like GPT-5-mini, the LLM only achieves non-zero reward for the shortest prompts, but the RLM maintains performance across a larger range of input sizes (uv run environments/oolong/plot_results.py -m prime-intellect/intellect-3 -I context_binned_by_subset):

The patterns are very similar as those seen with GPT-5-mini. Also similar are the number of prompt and completion tokens used for each subset (uv run environments/oolong/plot_results.py -m prime-intellect/intellect-3 -I tokens_by_subset):

INTELLECT-3 can maintain the RLM's average context window size, even though the RLM is tested successfully on far larger inputs than the LLM. The RLM's performance also scales with the number of sub-LLM tokens, at least on real data.

INTELLECT-3: verbatim-copy

uv run environments/verbatim_copy/plot_results.py -m prime-intellect/intellect-3 -I reward_by_content_type

Interestingly, INTELLECT-3 suffers from the RLM scaffolding for every single content type, unless it is given environment tips. Then, it improves its performance consistently with them.

RLM or long context attention for long running agent ?

Scaling attention to long context directly translate to more long running agent.

Scaling attention and context folding are a dual problem, both are trying to solve what to forget when looking at the past. One distinction is scaling attention try to solve this from a language modelling perspective. New attention architecture learn efficient attention during the pretraining or midtraining stage. Whereas context folding through RL learn how to manage its context via the outcome of the task it train to solved. .

We believe that both efficient attention and context folding are needed for true long agent. A better attention mechanism delay the context rot phenomena, and context folding allow the model to actively manage its context pushing the limit of what attention it self can do.

Summary and conclusion

Scaffolding to handle extremely long contexts is becoming more and more important to LLMs, and context folding is a promising approach in that direction. We currently believe that the Recursive Language Model is the best method for context folding, due to its simplicity and, at the same time, great flexibility and extensibility.

We implement a variation of the RLM in verifiers as the experimental RLMEnv, enabling plug-and-play usage in any verifiers environment. We ablate it with GPT-5-mini on four environments, and find that the RLM helps with long context problems and token-intense tool-usage. We validate our design decisions and find great promise for future training of the RLM.

We observe that the RLM scafold doesn’t necessarily improve baseline on all benchmark, we hypothesis that the true potential of RLM and context folding will be unleashed after being train via RL.

Future work

We plan to improve our implementation of the RLM further, and perform more experiments. Concretely:

- Right now, the RLM has a recursion depth of exactly 1. We plan on making it possible to decrease that recursion depth to 0 (so that we have a normal LLM with a Python REPL containing the input data, and access to all user-added tools), and to increase it arbitrarily, so that sub-LLMs can call further sub-LLMs

- We plan on making it easy for users to define custom functions for the RLM to use in its REPL

- While users can already install arbitrary pip packages, and the model is told about those packages, it might not always know them in detail. We plan on making it easy for users to add descriptions without having to re-write the entire prompt

- The RLM looks like a normal LLM from the outside: text comes in, text goes out. However, we plan on making context compression over multiple assistant-user turns a natural part of the RLM

- We will improve multi-modal support, and even custom data-types (the difficulty in them lies in the communication with the Sandboxes; we hope to solve this soon)

- We will train models to use the RLM, starting with small models

And of course, we will optimize the performance and trainability of the RLM, collect more metrics, and fix any bugs we find along the way.

.png)